Thanks to our special guest contributor Michael Strauss, an Accredited Genealogist from AncestryProGenealogists® for this informative article on military research using dog tags.

Behind the imposing gates of Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia rests the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. Around the clock, active-duty personnel stand as sentinels remembering our fallen veterans. Many cemeteries have remains of soldiers from past wars marked with a single haunting word, “Unknown.” To properly identify each man and woman who have paid the ultimate price for their country, the military created identification tags. Here is a look at how those tags have changed over the years.

Civil War

The Civil War changed how military officials recorded battlefield deaths. On April 3, 1862, the Adjutant General Office (AGO) of the War Department issued General Order No. 33, which in effect read: “To secure as far as possible the decent interment of those who have fallen or may fall in battle…lay off lots of ground in a suitable spot near every battlefield and… register of each burial and will be preserved”.

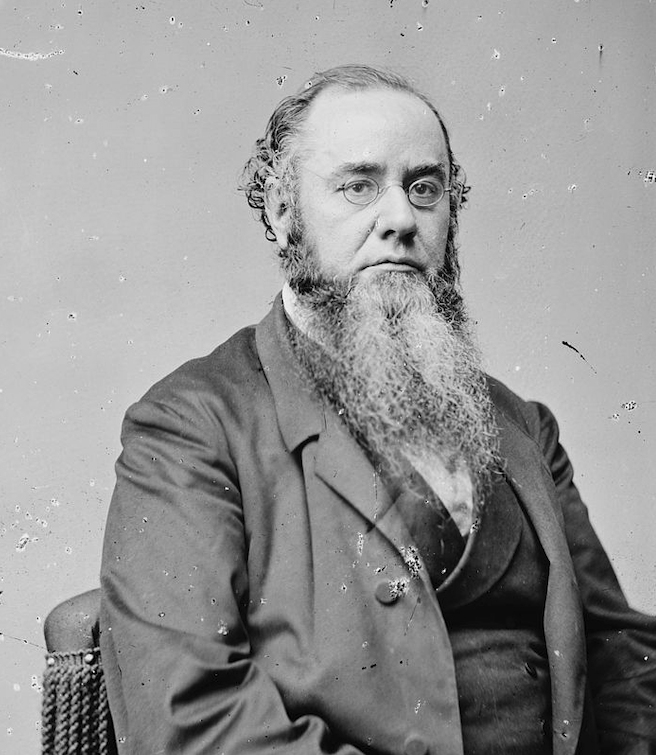

During the Civil War, large numbers of casualties on both sides prompted soldiers and civilians to consider other ways to identify fallen soldiers. In 1862, New York City resident John Kennedy wrote to the Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton. He proposed that the US Army provide a medal identification badge for all officers and enlisted men that soldiers could wear under the clothing. The War Department rejected Kennedy’s proposal.

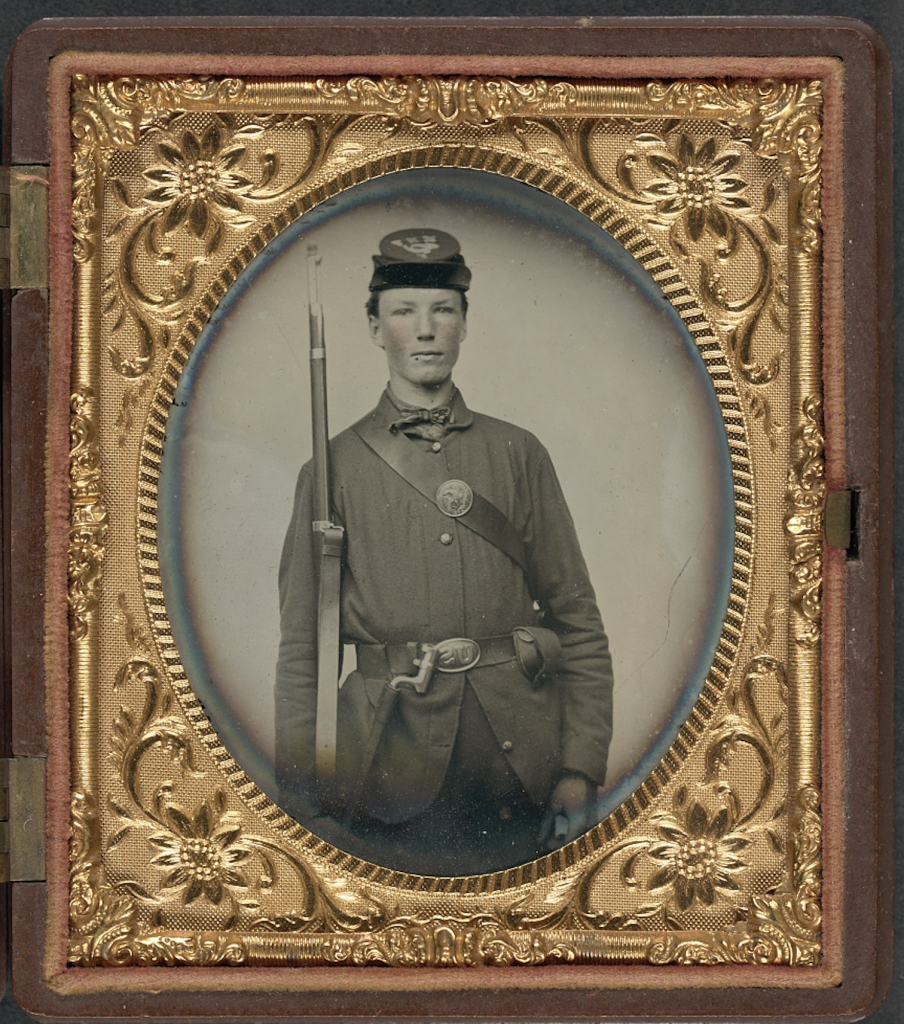

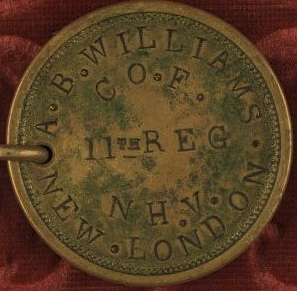

Civil War soldiers could purchase (at their own expense) identification badges or tags manufactured by military camp suppliers called sutlers. Sutlers were civilian contractors who traveled with the armies selling commonly needed items from photographs to wares. Some of these identification badges and tags were ornate in design.

Death became a reality for thousands of soldiers who had no proper identification. During the battle of Cold Harbor on June 3, 1864, soldiers, knowing they might be killed, wrote their names and military units on loose slips of paper, and pinned them to their kepis (caps) or sack coats. They hoped someone would identify their remains after the battle. Another 35 years would pass before the subject of identification tags was brought up again.

Spanish-American War

The War with Spain began on April 25, 1898, and again required the United States military to turn their attention to how to identify fallen soldiers. With fighting in Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines, the American Red Cross (founded in 1881) took up the cause to provide identification tags for soldiers. Neither the United States military nor individual states provided any identification tags at that time. The San Francisco Red Cross Society, one of the strongest advocates of tags, furnished them to thousands of soldiers en route to the Philippines. The tags were smaller than a half-dollar and made of aluminum.

The discs were inscribed with the soldier’s company, regiments, and a number corresponding to their eventual Compiled Military Service Record numerical identifier. On the other side of the disc was the visual design of the Red Cross, inscribed with the letters “RED.”

In 1899 United States Army Chaplain Charles C. Pierce was instrumental in establishing the Quartermaster Graves Registration Service. He wrote to the AGO office: “It is better that all men should wear these marks as a military duty than one should fail to be identified.” Pierce, a veteran of the Spanish American War, had witnessed the horrors of war and strongly advocated issuing identification tags for all soldiers in the military. Six more years would pass before the military adopted official tags.

Official Military Tags Introduced

On December 20, 1906, the US Army formally adopted Identification Tags when they issued General Order No. 204. The order read, “An aluminum Identification tag the size of a silver half dollar…stamped with name, rank, company, regiment, or corps of the wearer will be worn by each officer and enlisted man…whenever the field kit is worn.” Each tag had a cord attached through a small hole. The Ordnance Department provided each Army organization and unit with a steel die kit and two sets of dies, one for the alphabet and the other for Arabic numerals.

World War I

Following the entry of the United States into World War I on April 6, 1917, the United States War Department changed regulations on issuing tags. General Order No. 80, issued on June 30, 1917, read, “Gratuitous issues will be limited to two tags to an enlistment.” Soldiers were now issued two matching identification tags. An addendum called, Change of Army Regulations (or CAR) issued with General Order No. 58 on July 6, 1917, added, “These tags are prescribed as part of the uniform and when not worn as directed…will be habitually kept in the possession of the owner”, therefore making the soldier responsible for the care of the tags. They were to be part of their kits and always kept with them.

Another significant change to identification tags was issued with General Order No. 21 on August 13, 1917, when the military added, “The tag now prescribed for wear by officers and enlisted men will be worn also by all civilians attached to these forces.” Civilian employees attached to the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) would be authorized to wear identification tags. One final wartime change occurred on February 12, 1918, with the issuing of General Order No. 27. That order authorized service numbers for enlisted army personnel. The numbers were added to the identification tags.

Identification Tags for other branches

On October 6, 1916, the US Marine Corps issued General Order No 32, which read: “Hereafter identification tags will be issued to all officers and enlisted men of the Marine Corps… always be worn when engaged in field service…at all other times they will either be worn or kept in possession of the owner.” Initially believed to be of little importance, opinions later changed.

On May 12, 1917, the Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels issued General Order No. 294 stating: “The identification tag for officers and enlisted men of the Navy consists of an oval plate Monel metal…and suspended from the neck by a Monel wire encased in a cotton sleeve”. The Navy had more information added to the tags, which read, “The tag has on one side the etched fingerprints of the right index finger…the other side the individual’s initials, surname, month and year of enlistment [in numerals] …this side will also bear the letters U.S.N,” with officers it added: “Initials and surname, rank held, and date of appointment.”

The US Coast Guard issued Identification Tags authorized by the Chief of the Bureau of Navigation in Circular Letter No. 152-41 on December 16, 1941, which read, “The Bureau also directs identification tags be prepared and furnished the officers and enlisted men of the Coast Guard…the letters USCG should be stamped or etched on the face of the tag issued to officers and men of the Coast Guard”. In times of war, the Coast Guard operated under orders of the Navy, and they began to discontinue tags in the 1970s.

Between the World Wars

Following the end of World War I on November 11, 1918, the US Army made very few changes to identification tags until December 1, 1928, with Army Regulations 600-40 stating, “Tags are now officially part of the uniform and must be worn at all times.” From 1906 to 1928, tags were not officially considered part of the uniform. By the mid-1930s, identification tags were referred to by their colloquial name, “dog tags,” and were commonly worn by soldiers, sailors, and marines. The Army Historical Foundation wrote that newspaper editor William Randolph Hearst coined the term to undermine support for President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. Hearst heard that employees of the newly formed Social Security Administration were issued nameplates for personal identification, and he nicknamed them “dog tags.” There are other rumors of how the nickname emerged, but regardless, the history stretches back for decades.

World War II

In 1940, before the United States entered World War II, a major change was made to tags. Four new types were introduced for use during the war.

The first type came in December 1940 in Army Regulations (AR 600-35). It included a new shape and size and was made of Monel metal. It was two inches long by 1 1/8 inch wide and 1/40 inch in thickness. The tags included five lines of information:

- Name of soldier

- Serial Number and then added the blood type “A”, “B”, “AB” or “O” blood.

- Name of emergency contact

- Street address of contact

- City and State of contact

The second type, introduced in November 1941, made additional changes, including adding the religious affiliation of the wearer on the fifth line. Those designations were C for Catholic, H for Hebrew, and P for Protestant. This presented a challenge for service members who were members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The church, not considering itself Protestant, requested that the letters “LDS” be included. They contacted the War Department, but the request was not formally adopted. Some soldiers created their own dog tags that included the LDS designation. Thus, the five lines on this tag were:

- Name of soldier

- Serial Number and Tetanus immunization (Letter T and 2-number year and added 2-number year for when toxoid was completed) and also the blood type of the wearer with the following: “A, “B”, “AB”, or “O” type blood.

- Name of emergency contact

- Street address of contact

- City and State of contact/Religious Designation

The third type, introduced in July 1943, cut the lines down to three and included the following modifications:

- Name of soldier (with first name, middle initial, and last name)

- Serial Numbers, Tetanus immunization date, tetanus toxoid date, and blood type abbreviated.

- Religion of wearer (abbreviated)

The fourth type, introduced in March 1944, also included three lines and lasted until April 1946. It was nearly identical to the previous type, but the last name was listed first, followed by the first name, last.

One additional change occurred when a notch was added to one side of the tag. A myth began circulating that the notch was added for medical reasons, to hold open the mouths of deceased soldiers to prevent the body from gaseous bloating. In reality, the notch was created by the stamping machine.

In the years leading up to the Korean War on July 1, 1947, the tags were further modified and began adding prefixes as part of the serial numbers, with “RA” added for Regular Army.

Korean War

During the Korean War from 1950-1953, two styles of tags were used. One was for the US Army, and the other for the US Navy. The Army’s tags included these abbreviations:

- Prefix “RA” Regular Army

- Prefix “US” Enlisted Draftee

- Prefix “NG” National Guard

- Prefix “ER” Enlisted Reserve

- Prefix “O” Officer

These prefixes came before and were part of the assigned serial number (RA12345678). There were four lines on this tag, with the fifth left blank:

- Name of soldier

- Serial Number of soldiers, including prefix used for type of service

- Tetanus date and blood type

- Religious preference

The US Navy issued tags with three lines that included:

- Name of sailor

- Serial Number of sailors

- Letters “USN” and religion

Vietnam War

Several variations of identification tags were used during the Vietnam War. The first type, used through 1967, utilized five lines, and tags were no longer notched.

- Surname of soldier

- First name and middle initial

- Prefix and Service Number

- Blood type

- Religious Preference – Could be spelled out instead of abbreviated.

The second type issued during the Vietnam War was used from 1967-1969 with very little change from the previous type. They included:

- Surname of soldier

- First name and initial

- Prefix and Service Number

- Blood type (positive or negative could be listed), and number

- Religious preference – with the word spelled out

The third type used during the Vietnam War had effective use from 1969.

- Surname of soldier

- First name and initial

- Social Security Number

- Blood type – can be shown as negative (neg) or positive (pos).

- Religious preference – with the wording spelled out

During the Vietnam War, the US Marine Corps issued tags during the same period as the Army. The first type used by the USMC, was similar to the Army’s.

- Surname of soldier

- First name and initial

- Service Number, or if after 1972, the Social Security Number

- USMC listed, followed by the size of the gas mask worn (S-M-L)

- Religious preference – with the word spelled out

The US Navy also followed a similar style during the Vietnam War.

- Surname of soldier

- First name and middle initial along with blood type (positive or negative could be abbreviated)

- Prefix used and Service Number or Social Security Number after 1972

- Abbreviation of USN listing the branch of service

- Religious preference – with the word spelled out

Searching for records of burials of military veterans

Fold3® has several collections listing known military dead for different branches from the 19th and 20th centuries, where military tags were used to identify veteran remains. These collections include:

American Battlefield Monuments Commission

U.S. Veterans Gravesites, ca 1775-2019

World War II Army and Army Air Force Casualty Lists

United States Army Transport Service, Passenger Lists (including deceased repatriated veterans)

This list isn’t exhaustive, and other collections are available on Fold3® and Ancestry® that provide additional records of military dead for several different war periods involving the United States. Learn more about your military ancestors on Fold3® today.

I had ancestors who fought for our freedom again oppression in these wars: revoluntionary (many), Civil War (died at Andersonville), Spanish American (Uncle), WWI (grandfather), WWII (father-I have his ‘dog tags’) and Vietnam (cousin).

I know there are many others who fought and paid the (ulitmate sacrifice) for our freedom, but I don’t know who they are.

My father’s family the Plunketts had over 1,000 military all the way back to the 7 years war. 56 served in the WWII, 14 of those served their entire hitches in Europe; we had over 160 serve in the Un-Civil war from 9 states; we have 2 at the USS Arizona- the Murdock bros, plus 2 at the Vietnam Memorial- Kennedy & Plunkett.

I have found two (2) Civil War ID Tags while relic hunting with permission on private property. One was a soldier from the 37th Massachusetts Volunteers and the other was a soldier from the 83rd Pennsylvania Volunteers. I was able to get both soldiers military and pension records through the National Archives (this is back in the late 1990’s) and both survived the Civil War.

I am doing a project for our local Terra Alta Cemetery to identify veterans buried there to be able to lay wreaths as part of the Wreaths Across America in December. I realize it is HIGHLY unlikely but I have to ask . One of our veterans, Charles Reynolds Crawford was enlisted in the Massachusetts 37th, was wounded in the head at Gettysburg and left for dead. When they did a later sweep they realized he was alive and took him to the field hospital. They put a steel plate in his head. He wound up in Terra Alta WV. he had deafness because of the wound but was mayor of Terra Alta for at least 3 terms and died in May, 1901 from his wound. Is there any chance you found his tags?

Marilyn, my husband has family buried in the Terra Alta WV cemetery. It was surprising to see your post since it’s such an out of the way cemetery.

It is my hope that you will make effort to locate family who might treasure these tags for generations to come.

Rhoda, I also have ancestors buried in Terra Alta. I have Methany in my ancestry.

My ancestor was identified and found unclaimed on a shelf with his tags from the civil war. I am proud to say I had Major Isaac C Hart buried at Arlington National cemetery on April 27 th 2023 . One hundred and ten years later. You can look up on Arlington website and see his tags for yourself they remain on his can buried with him.

That is incredible!!❤️

Amazing! Thank you for that.

Sadly, we are now being forced to deny the Civil War era and our family heroes and families who lived and died during and after that major conflict in our country.

I read your story on the Arlington Cemetery website. It brought tears to my eyes. Thank you for honoring him.

Rachel,

I also looked up Major Isaac C. Hart on the Arlington site. I followed that up with a search on Ancestry.

You may be aware of this- there is a portrait photo of Major Hart through Ancestry and Find-a-Grave. It could be added to the Ancestry listing for him.

I have downloaded a screenshot of it if you’re interested.

Cheers,

Henry

@ V. Zeeck

Nobody is “denying” the civil war era. We just don’t want people honoring the losers who tried to fracture our country and continue to enslave people, just to prop up their agrarian industry in the world market by means of cheap labor. So down with the statues and memorials. . .

Thanks for your post, Rachel!

Sadly, the reply by ‘Commander Cody’, who suggested that we’re only allowed to honor the lives of past soldiers if they match current politically-correct opinions, is part of the kind of reasoning that leads to war in the first place.

I can see him and his ilk out there vandalizing graves.

Serial numbers also used the designation N for nurses.

The major change in the ID tags that happened during WWII, was because the destructive forms of death greatly increased and it was realized by Graves Registration in Africa that a “brewed up tank, held bits and pieces of destructed bodies and useless ID tags, as they could not stand the heat and destruction. Thus Graves Registration could not determine exactly who was in such a mode of death. Upon this realization, research was conducted at an Army base, where they asked for the remains of young men who had died for any reason to be turned over to the Army for secret research. The dead were inducted in the Army and given military funerals after the testing.

Fully loaded tanks were placed in a target range with the “in uniform” dead bodies in the position of the normal tank crew. Then, different medals were used to create test ID tags, that were placed on human remains. Then, the tank was fired at to create an actual combat type “brew up.” Of the tested metals, a stainless steel ID tag withstood the “brew ups” and in the future, Graves Registration could used the surviving ID tags to ID the crew men in a Tank.

A war time Graves Registration friend of mine, told me about how one tank was “brewed up” three times. During the first, they were short of an ID tag for a supposed crew member. That tank was repaired by a forward tank repair unit and some days later, they got another call for a “brewed up” tank at the repair unit. This time, they found ID tags to account for all the members. Then, a little later, they got a call and found the same tank and were able to account for the dead. A couple of days later, they got a call from the repair unit and were told they had missed a recovery. The repair unit had removed the bottom flooring of the tank for repairs and they had found an ID Tag. Yes, it was the missing ID Tag from the first “brew up!” So, back to the repair unit to pick up the ID tag, while there they swept some human material from the newly opened area and created an “Identified,” no longer Missing In Action remains.

If, one researches it, you will find most group burials took place later in the war and often, created by newer GR people. As the GR men told me at one of their reunions I went to, that they would not want their mother to be told, that her son was dead and he could not be identified. So, though Regulations called for such group deaths to be placed in a mass burial grave, they made sure each found ID tag was placed on a GR Ditty bag and some ashes and bone fragments were placed in the bags to insure the mother would have a true grave for her son during future visits.

Having interviewed many Graves Registration men before their “final transfers,” I learned that every story they told was true and I never caught one embellishing a story, unlike many others I have interviewed in the decades now past.

You need to write a book.

During my second tour in Vietnam I was assigned duty as Platoon Sergeant for the Provisional Rifle Company providing security for Camp Books, Red Beach, DaNang RVN. If one of my Marines was caught sleeping, or not attentive, on duty I would assign them temporarily with the Graves Registration Platoon in DaNang. It only took one assignment to convince them to stay awake and alert because every other Marines life depended on them.

A very interesting article!

Funny how I’ve always been able to remember my number.

One thing that re-enforced it for me was the exercise where they were training us to use our gas masks. We were placed in a small room and subjected to either tear gas or CS gas (pepper spray). Upon being told to exit the room, the subject had to remove their mask and scream out their Serial Number. If you stumbled through it, you got to repeat it. The effect being that the Serial Number became indelibly inprinted on your brain!

Thanks for an interesting history of the ID tags.

Specialist Gene McAvoy, US Army Signal Corps

RA11580213 – still remembered well even at 77 years old.

Gene, I remember the exercise well. We were told to memorize our serial number on the trip to Ft. Polk…RA15925796 at 77.

Fascinating article!

Gene — I’m a few years older than you, but had the same experience. My SN is etched in my mind, not just on my dog tags.

ROTC commissioned, USAR, Military Intelligence.

After returning from Vietnam, I was near a protest on campus where CN or CS was being used. Friends asked why I was moving away from “a little cloud.” I saw them the next day and they asked how I knew about that stuff!

Thank you for your service Gene.

Cindy Taylor

Did the same thing at Ft. Dix in late 1961.

SP 4 Edward Jenest, Medical Service Corps

RA11399105 will never be forgotten.

May 1959, Ft. Leonard Wood, week # 1, NG 26247551, SIR ! To this day at the V.A. Hosapital when they ask for my Social, I catch my self using the wrong number!

Larry H. FAG # 47183068, Social — — 3486, PIN numbers, (Our life is full of numbers!)

Funny you should mention remembering your enlisted serial number & why, because I too remember mine, assigned in 1963.

Thanks for the memories.

Having had a Father who served in WW2, this was a very interesting article! Dad was shot through both legs during the battle on the island of Iwo Jima. Those dog tags identified him. He proudly wore those battle scars the rest of his life.

I an a Navy vet from the Korean War days. My dog tags have J for Jewish, not H for Hebrew. Don’t know the reason for the change.

During my Marine boot camp visit, the dog tag guy asked me what my religion is. I could not remember (Episcopalian), so he put down Baptist and that is what is on my tags today. He decided. Today I say agnostic.

Israel got founded in like 1948, probably why the change was made. Everyone became Jewish (not Hebrew..)

WHEN I WAS IN THE ARMY (1957 – 58) WE WERE TOLD THAT ONE OF THE DOG TAGS OF A COMBAT DEAD SOLDIER WAS TO BE PLACED BETWEEN THE TEETH OF THE UPPER & LOWER JAWS. ONCE THAT

IS DONE THEN KICK THE CHIN WHICH WILL SET THE TAG FIRMLY IN THE DEAD SOLDIER’S MOUTH ‘TILL THE GR GUYS PICK UP AND DISPOSE OF THE BODY. THE OTHER TAG SHOULD BE TURNED OVER TO THE PLATOON LEADER OR THE FIRST SERGEANT THEN ON TO THE GR PEOPLE.

That is exactly how my stepdad explained it to me- word for word

Correct. I was told when I served, that the notch at one end of the dog tag was put there to hold the tag in place before securing it so it would not slip out.

@ Commander Cody

We are all Americans and I served for all. What happened in the Civil War – happened. We were not alive then, we are alive today based upon what was done in the past. Statues and Memorials honor those folks who fought for their cause at that time. They stand the test of time and bring that memory into today. Right or wrong, it’s a constant reminder to NOT do it again. Defacing, destroying or removing those reminders is disrespectful and not the reason I served my Country. It is important to retain our Country, so we can have the right to voice our opinions rather than be under the control of a dictatorship or faction that is mandating what we are told to say and do.

For those interested in further details on how dogtags have changed since WWII this website has a great historical timeline showing how they differ between military branches and eras.

https://www.mydogtag.com/dogtag-timeline.php

When I was issued my tags in Navy boot camp (1962), my serial number had 7 digits with no repeating numbers. It seemed easy to remember. When I retired (1991), I was still wearing the same set of tags even though the DoD started using SSNs in 1972. At one point in my career, I was assigned the task of making dog tags at the base on Treasure Island (San Francisco) for those draftees inducted there in 1967. I also have my fathers tags from WWII. I have been a genealogist since leaving the Navy and with the help of Ancestry.com, and all it’s branches, I have been able to fine many of my former shipmates. Even sadly, with the help of Fold 3, I have found some who left us way too soon. Thank you all who are dedicated to the preservation of those who served.

I read this with great interest and fetched my father’s tags from WWII. He joined the Army Air Corps which obviously became the USAF. His tag read his last name then first, then under that his ID # then T 44-45 and O. I see no mention of a two line tag in the above review. The T 44-45 is the Tetanus designation/dates and O was his blood type. The ‘notch’ mentioned is indeed at the ed of the two lines of data, and down in the lower right corner, under the hole for the chain is a P, he was indeed a Protestant. I have two of these, both identical which he saved with his patches and ribbons and pins. Knowing the story of the tags was very interesting and a subject, that even as a genealogist, I had not thought to research. Thank you for this!

Hi Richard, I wanted to share the information on my dog tags. I served during the Cold War and early Vietnam Era (the US served as advisors, and we had casualties at that time). My tags read: 1st row: last name, 2nd row: first name, 3rd row: AA followed by my 7 digit serial number. 4th row: T59 Tetanus in 1959 and O POS for blood type. Last line: Greek Orthodox.

I too have a deep interest in genealogy. I’m a first generation American of Ukrainian descent. I had listed my religious preference as: Ukrainian Greek Orthodox, but of course in the 50’s-60’s, we Ukrainians were defined as “White Russians “ which I always found offensive. Now everyone knows where Ukraine is. Thanks for letting me share with you.

As a young teenager (13?) in the late 60’s, I would go to work with my dad during summer vacation. He worked in the PAC office at Ft Meade. I was sent to the first floor where a wonderful lady taught me to make dog tags. The machine I used is now on display at the National Museum of American History. I saw it after I was married and had kids. (You have to look hard to find it! Or Google it to see what it looked like.) So glad they preserved it. My salary for that work? A box of chocolates…perfect payment. It was fun to read the history of something I used to make.

As a 20-year old draftee from southern California I received 16 weeks of infantry combat training before deployment to Korea where fighting was fierce. That is where most of my training company was sent but I was sent to Ladd AFB in Alaska, but that is another story. Some years later as a civilian I lost my dog tags. They had been so important during my two years of active service that even now, at 89, the feeling of loss remains. There is a museum now at Camp Roberts and in it is a dog tag machine. I declined to buy a tag because it would not have had the original identifying information nor the notch.

Nurses who enroll with the American Red Cross receive a pin with their enrollment number engraved on the back. In WWI, this was used to identify the Red Cross nurse in the event of her death.

I remember the gas training like it was yesterday 53 years ago. Many of my fellow soldiers gagged & upchucked after being told to repeat their names, rank & Social Security number. I enunciated loud enough that thankfully one time was good enough for my Smokey the Bear!!!

Like others on here my relatives go back to the Revolutionary War with my late father oldest of 10 serving with the Navy during WW II, a younger brother of his dying in the Navy and another younger brother serving underage with the Merchant Marine.

I remember around in February 1952 New York City School systems issued dog tags to the students because of the Cold war with Russia and nuclear bomb, Duck & Cover.

I was in 3rd grade when WWII began. Our school in Los Angeles was just across the L.A. River from the Southern Pacific RR. yards and roundhous – a strategic target. All of us children were required to wear a tag made of sterling silver. On one side was my name. On the other side was my father’s name and phone number.

Is it possible to get duplicate tags? My daughter’s father passed away recently and she can only find one of his tags.

Yes, you can order era and branch specific reproduction dogtags from https://www.mydogtag.com/military

My father was a vet from WW2, Viet-nam and Korea (purple ). I recall we had to memorize his service number as children. He was initially a reserve officer and his number was 01335788. Upon receiving a regular commission his number was 080869. Even at 80 years old, I remember his and of course my number…RA13737402. AIRBORNE

ALL THE WAY!

As a follow up, does anyone know why we were required to memorize the parent’s service number?

I am a woman veteran, (WAF, USAF) serving from 1959-1962, now nearing my 83rd year. I’ve never forgotten my serial number and still have my dog tags. A couple of years ago I called my HMO to make a medical appointment and was asked for my medical number, which I also have memorized; I rattled off a number. After a search I was told my number couldn’t be located. I’d given my serial number. When I explained we had a good laugh. Of course if you asked me what I did a day ago, I might not remember.

I grew up in a suburb of Pittsburgh in the early 1950’s. The city was considered a valuable target because of its steel mills. I remember the duck and cover drills and still have the dog tag that was issued to me. One of the buildings in the city flashed out Pittsburgh in Morse Code. Of course that had to be turned off as well as the highly recognizable Three Rivers and surrounding areas blacked out.

Most likely because if you had to fill out a form, or needed medical care, you’d need your parent’s service number. I know that now my wife’s medical record is linked to my record, because she derives her entitlement to care from me (retired Army).

I would be interested to know if there is information for countries other than the United States anywhere.

Proud daughter of a Canadian WWII veteran here.

I would like to Thank the Person who gave the link for the U.S., World War II Hospital Admission Card Files, 1942-1954 at Ancestry.

For years I have tried to find information on my Dad’s twin brother who in WWII died in North Africa. I found the information regarding his grave in Carthage, Tunisia, but not his or why he died except it was listed in an index, as DNB.

Of course his information was one if the casualties of the “Fire of 73”

The link to Ancestry had his admission record and stated his cause of death

“ Diagnosis: Burns; Location: General; CausativeAgent: Mine, explosion of

Injured in Line of Duty In line of duty“. Although his intermittent record says decoration “none”, would there have been some recognition that he died in the line of duty? And if all his other records are gone wouldn’t he have been issued some medals like hood conduct, WWII, Foreign Service?

Thanks again..and if anyone wants me to look up the records in Ancestry, I’d be happy too. email: [email protected]

In 1940, French and German soldiers had a plate to put on with a cord around the neck. The Belgians had it on a bracelet (the risk of losing it was greater – now it is also on the neck with a chain). But all had a big difference with the Americans who had two medals: it was a single plate with the inscriptions in duplicate separated by a dotted line which made it possible to break the plate in two.

Correction: the French had it as a bracelet in 1940 (a plate to be cut in half).

“DNB” stands for “disease and non battle injury.”

It would imply that he was likely killed by an American mine, perhaps in a rear area. It would also imply he was not entitled to a Purple Heart. But the notation could have been in error.

Now, the Purple Heart is a decoration. All of the other awards he would be entitled to are considered Service Medals, not Decorations.

Check on archives.gov for who/how to file for earned service medals-they’re limited to certain family members-and they will figure out the rest, based on units of assignment and dates.

Oh, and if he was awarded a Combat Infantry Badge or Combat Medical Badge, he would have been awarded a Bronze Star Medal after the war automatically. But you have to ask.

Thank You for that information

But if his records are no longer in existence how can I find out?

Fabulous article and comments! Many thanks to all who have participated in our education.

Frances Austin: They have alternate ways of recreating records. For example, if the burial record says what unit he was in when he died, they can trace backwards in morning reports to see when he joined the unit. It’s easier for some units than others, of course. If he was drafted into an infantry unit, he might have been in the same regiment the entire length of the war. They know the date he entered, the date he was killed, and the date the unit moved from place to place. WE know, for example, that he’d be qualified for a good conduct medal, absent proof he was disqualified–that’s automatic. He’d be entitled to the World War II Victory Medal, and the European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal. Depending on how long he was in before his unit went overseas, he might qualify for the American Campaign Medal (you have to have been in the States for two years to qualify for that one). If he was drafted during the Peacetime Draft, or just enlisted prior to 7 December 1941, he’d qualify for the American Defense Service Medal. All of those are based simply on time and location. Depending on when he got to Africa, he would be authorized one or more campaign stars on his EAME Service Medal, and possibly an arrowhead.

And his unit may have been given unit awards, such as the Presidential Unit Citation. But again, if you were assigned to the unit during the time period covered, it’s automatic. There are books (regulations/DA Pamphlets) that you can look them up in.

It gets more complicated if he transferred from unit to unit, or if he was an individual replacement.

That’s why you file a specific request asking to be issued his service medals and awards. Then they have to look them up and issue them. But it helps if you provide them as much information as you can with your request. Make it hard for them to say “too hard to do.”

Do you know what unit he was with, and when he served with it?

Also, if you know the unit (especially if it’s one that’s still active, or was a major unit, like a division), you can see if they have an active Veterans’ association. They usually have a historian, and may maintain casualty lists, unit rosters, etc. which can help you in determining some of that information.

I can’t remember what I had for diner last night but my but my Army dog tag # was US 56238975

I am 90 and was in the Army 1954 to 56

I am 90 years old s/n US53172357

Bless you, sir

You can find more on Spanish American War dog tags (examples of other styles) at https://spanamwar.com/dogtag.htm

My grandfather’s navy dog tag (circa 1907) actually has his thumb print in the back. Somehow they etched it in

I am so impressed by all these comments. I am in Canada and finally found all (or most) of my uncle’s war service, etc. He was a sharp shooter and won quite a few awards. All this I found by going on Newspapers.com (usually is offered free over some holidays), typing in his name and came up with half a dozen short stories that he was involved in. My father was in WW2 and I polished many a button on his uniform. I found a number of his buttons in my mother’s button box and have cleaned them up and put them in a frame. I don’t recall dog tags but I shall have to check our Canadian units to see what they wore. Many thanks for all the stories, etc. My mind is totally boggled and I will now start doing some research on dog tags. As I am now nearing my 87th birthday, I shall have to get a move-on and see how my stories I can put together from all the records that are available. Thanks to all who served and to those who waited at home.

My sister’s father-in-law was captured by the Nazis in WWII, amnd sent to a POW camp. He made sure to “lose” his dog tags, which identified him as Jewish (H).

There is an excellent article on the dilemma faced by Jewish soldiers in the ETO during WWII:

https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/jewish-american-pows-europe

The family’s address was removed because some were making dishonest offers to the family but it allowed my mother and my aunt to correspond with the family of a GI killed at the Liberation in our village in Belgium in September 1944, to explain to him the circumstances of their son’s death and to send them photos of the deathbed, of the procession to the church and to the cemetery and his burial.

How wonderful, Jean-Luc. My husband and I have traveled from the US to once again visit the graves of our family members at Henri-Chapelle, this time for the Memorial Day ceremonies. We are so grateful to count as dear friends the Belgians who have adopted (“Sentinels”) the graves. It means everything to know they are not forgotten.

My Dad’s WWII tags were stolen in a burglary of our home about 50 years ago. He’s no longer with us, and I got the idea of ordering duplicates, but I can’t find any record of my Dad’s blood type. Medical records generally do not contain it, and most of his military records, including his medical records, were destroyed in the infamous warehouse fire. Any suggestions where I might look? Also, how would I know which version of the tags he would have had? Would it be based on when he was discharged or when he enlisted or when he was promoted?

Soldiers who were prisoners in Germany during WWII received a German plaque with duplicate information that could be broken along the dotted line.

Upon the death of the person, the tag was split. One went up stream to account for the death, the other was placed on the grave marker. While doing research in France, we recovered several German half ID Tags.

Research found, that a German artillery had been stationed on the hillside where we found them and there were graves there when the first civilians came back after the war. The half tags had been nailed on the markers and apparently, when the German recovery teams came and removed the remains they discarded the half tags, all of which had nail holes in them.

Due to the soil condition, the metal did not last long when in contact with it and, of course, the markers were easily destroyed when further battles raged over the area.

Thus, a reason, like the English and French, so many of their cemeteries have many Unknowns. In German and French cemeteries, when visited, one will find markers stating a number of dead were buried there. Sometimes, over a thousand or more.

This information is very informative and interesting! I had no idea how the identification tags were started and their evolution! Thank you for this very fascinating data!

I have my grandfather’s tag from World War 1 and also my tags from Vietnam. USMC 1967-71.

My Mother had secured a stainless steel bracelet of the same information for my father during his Merchant Marine Service in the Second World War. I have this valued bracelet too.

Semper Fi!

USMC 1964 – 1967.

Someone please change the word internment to interment in the second paragraph of this article, even though it is a quote . The two words have very different meanings.

I have dog tags even though I never served in the military; but my father did. I was born in Germany while my father was serving during the Cold War. Children received them in case there was a conflict?

Anne Wells: We had plans to evacuate family members in the event a war started, called “Noncombatant evacuation operations,” or NEO. I suspect they were tied to that, plus helping identify you if you got separated from your parents.

I am a retired Army Master Sergeant E-8. I would like to share some information. My third great grandfather, Michael Wolfgang, fought two tours of service in g the Revolution. His son, my second great grandfather fought in the War of 1812. Both received land grants in Pennsylvania for their service. My father’s grandfather fought in the Civil War, in Virginia in 1865. A number of other ancestors fought in WW1, WW2, And Korea. Between my three brothers, my sister, my son-in-law, and myself, we have over 100 years service during the Vietnam era. I like to think that my family earned this wonderful country for my family and me. We are so !lucky. By the way, I still have two sets of dog tags, one with my service number, which I still remember, and one with my SSN.

Jerry Swartz: Use the information at the time he enlisted. I wouldn’t worry about the blood type, most people wouldn’t notice.

He wouldn’t have been issued new dog tags when he was promoted or reenlisted except in two cases: If he was commissioned as an officer, he would receive a new Serial Number, and if he reenlisted (which would have been after the war–if you were drafted, it was “for the duration plus six months”), he would have switched from a drafted status to Regular Army, which would also have changed his serial number to one prefixed by “RA.”

If you have a copy of his discharge papers, his blood type might be on them.

My name is Hans Radojewski, I am 76 years old, I live in the Netherlands. After 76 years I finally found my biological father through a DNA test: James Bailey Housley

(Johnny) found. He fought in the US Army. At the 73 armored field arillery Battalion of the 9 DIV. He is trained as a medic. He had his training in 1942 at Camp Forrest and Coffee. On his return from the war he died in a gun incident in Tennesse in 1950, I was 5 years old then, I would never get to know him. I would like to get in touch with people who can tell me more information about him or his service.

e-mail . [email protected]

thank u

I am a graduate of Virginia Military Institute and have a Brother Rat who has made a lifelong study to find and record the graves of the 257 Cadets who participated in the Shenandoah Valley Battle of New Market. Those who were killed are known and all but one is interred at V.M.I. The others who lived long lives are scattered around the globe but most are in famlly plots—often with no marked stone—throughout Virginia. He has found and purchased stones for several who died with no fanfare. All of those teenage Cadets fought for defense of their state and nation as Mr. Lincoln invaded the Southern states in a like form of George III in the 1780s.

History is full of those who destroyed memorials of those who lost, and in historical time, it was not long before it was their memorials being destroyed. All such memorials are important, for without them, those who do not know their history, repeats their history.

For many years, such hate in the United States was slowly melding into a new, wonderful world where people worked together, no matter their race background. However, now the sickness is being brought back to the surface, so those who want to destroy the United States Of America can succeed.

@Willis Cole

Amen to your statement. Glad to see there are still true Americans out there that respect all that we have been through as a Country. It is sad that in a well presented and informative discussion on dog tags, that this cancer has to surface. We need a true leader for our Armed Forces and for our Country – next election cycle. Spread the word and let’s all vote legitimately for the people.

My late husband was in the Army, 82nd Airborne Division from 1975-1979.

His dog tags had his name, his service number, his blood type, and his religion, Methodist.

He said the reason for two tags was so one would go with the grave detail to have the death officially recorded, and one would go with the body, shoved between the teeth to make sure the body is correctly identified.

My dad was a Marine in Korea, one of the Chosin Few. I have his dog tags. There are four lines: 1) Last name, 2) First name, middle initial; 3) serial number; 4) BT-A-P. I am assuming the A is for blood type and the P is for Protestant, and I think the T stands for tetanus toxoid, but don’t understand what the B is for. Can anyone give me a clue?

Jacque: Blood types come as negative and positive, and it’s very bad of you mix them up. It’s more likely that the line stands for “Blood Type-A-Positive”

LOOKING FOR VERIFICATION OR COMMENT ON THIS:

My father was a map maker in WWII. He landed at Normandy a couple weeks after D-Day and advanced with his unit through France, Belgium and Germany.

He told me that, when a soldier died, the dog tag that stayed with the body was stuck in the eye socket.

I have not read about this practice anywhere. I was interested in the comment above about how the dog tag was put between the teeth of the deceased.

Does anyone know about the practice of sticking the dog tag in the eye socket?

I met many Graves Registration men over the years. It was not standard to place the ID tag in an eye socket, as that would have required them to greatly damage the eye of the dead who had not been rotted. It sounds like your father’s advisor may have met someone who told him, the story he had been told. As to the rotted, often in the process of rotting, the ID tag would sink into the mess and I have met, several men who discussed having to retrieve id tags for remains like that. One tagf and one tag was kept with the remains when recovered. In that case, I can see some GR men placing the ID tag that stayed withe remains, placing the ID tag in the skull, via the eye socket to insure it was accounted for.

When recovered and buried in a temporary cemetery, each remains had a well sealed green bottle placed with it. In that bottle was all the information concerning the deceased to insure correct identification.

During the Final Disposition of the WWII dead, when each remains buried in a temporary cemetery, or field found, the remains would be searched. “…the processors searched the remains for identifying media, such as tags buried or embedded in the flesh of the posterior parts of the shoulder girdle.” I have been told, in the case of Unknowns, the search checked out all remaining parts of the body, that might hide an id tag or other possible identification information.

“Final Disposition Of World War II Dead 1945-51,” page 618

“When the processors found two identification tags, which should have been worn around the neck, they fastened one tag to the the blanket near the head of the remains and tacked the other one to the head of the casket in the upper right corner. When they only located on tag, the laboratory workers pinned it to the blanket and an embossed strip was cut and placed on the head of the casket.”

I have the ID tag of a Congressional Medal Of Honor awardee that was removed from his coffin at the time of his official and final burial. The family siblings gave the tag to me for sharing my research into his crash, death, and full knowledge of all my connected research.

As to the Graves Registration men, often their actions depended on how long they had been GR men and recovering remains. The earlier, the more men who died to together had remains collected and divided to insure individual graves, so their mothers would not know just how they died. Toward the end of the war and especially afterward, such death combinations were placed in one grave with all the names listed. Over the years, the parents of deceased that I talked to and told them the truth, all agreed they preferred what the earlier men did, instead of having to visit a combination grave and wonder all their life, if their son was really there.

One of my uncles that served in WWII did not have a birth registration (born in 1924 – doctor must have forgotten to file some paperwork). He managed to enlist in the army, worked his entire life until retirement with no birth certificate. Then he needed to verify his age and service for his pension. My cousin worked very hard to do this, taking statements from old timers who knew him as a child, school records, etc. When my uncle came up to visit my dad, the two of them recited their names, ranks, and serial numbers. My cousin had never thought to ask him if he knew his serial number. It would have made accessing his army pension a whole lot easier!

My grandfather’s, my father’s and my dog tags which were all on my key ring which was stolen along with my purse. I was sick about and wish I could find a way to recover them.

Michael- Is that John Kennedy, the resident of NYC who you mention suggested tags back in the Civil War time, John A Kennedy who became the police superintendent of the city?

Love to learn what reference you have for that fact as John A Kennedy is my third great uncle.

Always great to learn fun facts, Laura Hobbs

Thank you for the fascinating details of the history of tags. We have here (the UK) the tomb of

The Unknown Soldier, so the tags are important.

Joanna

The United States also has a Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia near Washington, D.C.. The remains of an unknown soldier from World War I is interred in the tomb (details from Wikipedia below) and he is the recipient of the Medal of Honor and the Victoria Cross among other awards.

One Unknown each from WWII, Korea, and Vietnam are nearby in other monuments.

On Memorial Day, 1921, four unknown servicemen were exhumed from four World War I American cemeteries in France, Aisne-Marne, Meuse-Argonne, Somme, and St. Mihiel. U.S. Army Sgt. Edward F. Younger, who was wounded in combat, highly decorated for valor and received the Distinguished Service Cross, selected the Unknown of World War I from four identical caskets at the city hall in Châlons-en-Champagne, France, on October 24, 1921.[5] Younger selected the World War I Unknown by placing a spray of white roses on one of the caskets. He chose the second casket from the right. The chosen Unknown was transported to the United States aboard USS Olympia. Those remaining were interred in the Meuse Argonne Cemetery, France.[5]

Martha B. Higgins: Actually, the crypt for the Vietnam Unknown is empty. They had interred an unknown, but he was later disinterred and identified using DNA as Captain Michael Joseph Blassie, United States Air Force.

It is unlikely that, because of DNA technology and modern forensic techniques, that we will ever have another unknown soldier.

You can read about Captain Blassie, and the story behind the identification of his remains, here:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michael_Blassie

I was aware that Captain Blassie had been identified, but there is still the Tomb of the Unknown for that era, not now called the Vietnam memorial, even though it is empty. It is comforting to know that with modern forensics and DNA that there will probably not be another Unknown

The truth of selecting the “Unknown” soldier began long before this ceremony. A team was selected to go to the battle fields and search for “Unknown Soldiers.” However, they were under very strict instruction to insure they did not recover a remains of color, or even the possibility of another nation’s Unknown Dead. They passed over a number, before final selection of the accepted “Unknown” was made.

The location the selection is available for a tour at the fort in Verdun. Before it was a most interesting “walk around” visit and then, it become a very controlled trip through the fort and back out.

The same has happened at the “D Day” Anniversaries. At the 50th, I danced with the French in the parking area below the steeple where the American Parachutist was stuck. Then, at the exact moment of the first landing of the Americans from the air, the U.S. National Anthem was played and the partying began. I could not get in as an American, so a French Memorial Group enlisted me and took me with them. When done at the park, I went a bar with my French friends and met the General and leaders of the parachutists.

At the 60th, it was becoming commercialized and too organized, even in the same village.

At the 70th, we stayed with some French friends on Utah Beach and have decided, we would no longer go on the actual Anniversaries, but a few days earlier or later, as the fun and real Memorial part of it was gone. Now, at my age and the 80th next year, we are even beginning to question going at all.

What with all required inspection points to insure safety, where one used to walk, enjoy and Remember. The Veterans I had met who invaded the beach that day, and especially the Graves Registration men who did land that day, though not given credit. As they were not allowed to recover the newly dead, they were ordered to travel up to the fighting line, carrying machine gun ammo. They were not realized that day, until in the evening to begin their assigned task of recovering the dead. Thus, you see men walking past the dead to go to battle, instead of believing there was a good chance of life ahead, what did they have to think?