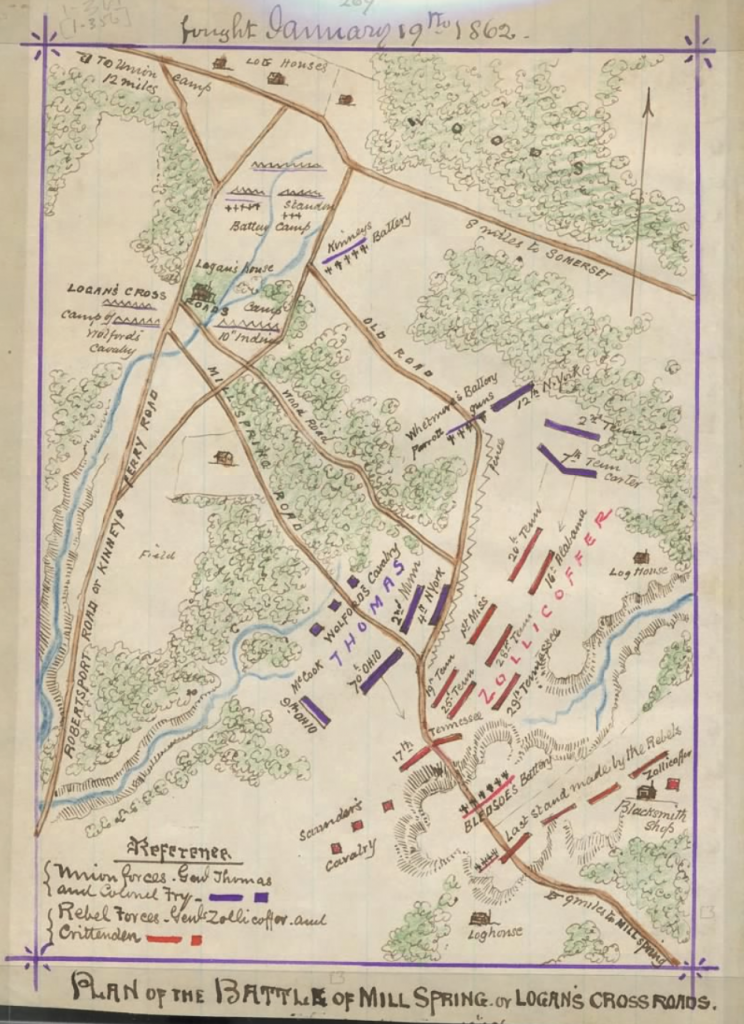

On January 19, 1862, Union troops experienced their first significant Civil War victory during the Battle of Mill Springs in Kentucky. The battle, also known as the Battle of Logan’s Cross-Roads (in Union terminology), and the Battle of Fishing Creek (in Confederate terminology), occurred in Pulaski and Wayne Counties near present-day Nancy, Kentucky. It resulted in Union troops breaking through the Confederate defensive line and opening access into Middle Tennessee.

At the beginning of the Civil War, Kentucky declared neutrality, refusing to align with either the North or the South. By late 1861, the Confederacy had established a long defensive line, running from Cumberland Gap across the southern part of Kentucky to the Mississippi River. After a failed attempt by the Confederacy to take control of the state, Kentucky threw out its neutral status and aligned with the Union. Abraham Lincoln, a Kentucky native, was reputed to have said, I hope to have God on my side, but I must have Kentucky.”

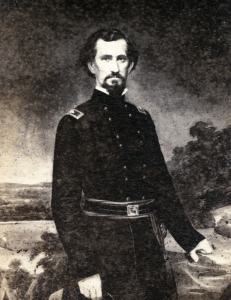

In November 1861, Confederate Brig. Gen. Felix Zollicoffer wanted to extend the Confederate strategic defensive line by moving north and establishing his winter headquarters near Mill Springs. He hoped to shore up defenses to prevent Union troops from advancing into Middle Tennessee.

At about the same time, Union Brig. Gen. George H. Thomas was advancing towards Somerset, Kentucky (about eight miles from Mill Springs) with roughly 4,400 Union soldiers. His goal was to rendezvous with reinforcements and push the Confederates out of Kentucky.

Hoping to attack before reinforcements arrived, General George B. Crittenden, area commander for the Confederate army, ordered Zollicoffer and roughly 5,900 Confederate troops to advance. They started marching towards Logan’s Cross-Roads just after midnight on January 19th. Heavy rain, deep mud, and cold temperatures made the six-hour journey difficult.

At 6:00 a.m. on January 19th, with driving rain, dense fog, and limited visibility, Confederate forces attacked. Fighting was fierce and the weather added to the chaos. The Confederates achieved early success but were repelled by Union forces who had far superior weapons. During a lull in the fighting, Zollicoffer approached a Union company. Assuming they were his men, he ordered them to cease their fire. Union troops recognized his Confederate officer’s uniform and shot and killed him.

After the loss of their leader, Confederate troops became disorganized and fell back from the center of their line. As Union troops surged forward, the Confederates were defeated and forced to retreat across the Cumberland River.

The Union victory at Mill Springs resulted in an estimated 262 Union casualties (including 55 killed) and 552 Confederate casualties (including 148 killed). The battle created the first break in the Confederate defensive line that would ultimately lead to Union operations in Tennessee and Mississippi. To learn more about the Battle of Mill Springs and other Civil War battles, search Fold3 today!