In September 1940, as Nazi bombs rained down on London during the Blitz, America began the first-ever peacetime conscription and enacted the Selective Training and Service Act. The country was moving closer to war and the Sullivan family of Waterloo, Iowa, answered the call. That fall, Joseph Sullivan, 22, registered for the draft. By the following summer, the other four Sullivan brothers – Albert, 19; Madison, 21; Francis, 25; and George, 26; also made the trip to the Federal Building in Waterloo and filled out their registration cards. The Sullivan brothers insisted they serve together. Weeks after the attack on Pearl Harbor, they enlisted in the US Navy.

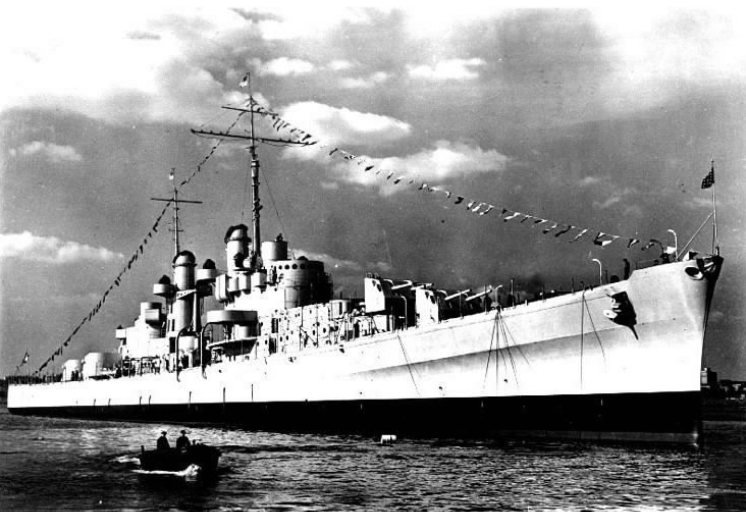

All five brothers were assigned to the USS Juneau. Juneau was part of Task Force 67 and sent to escort a resupply convoy to Guadalcanal. The Battle of Guadalcanal (codenamed Operation Watchtower) was an offensive aimed to protect critical supply and transportation links between the United States and Allies in Australia and New Zealand. It was the first major offensive against Japanese forces.

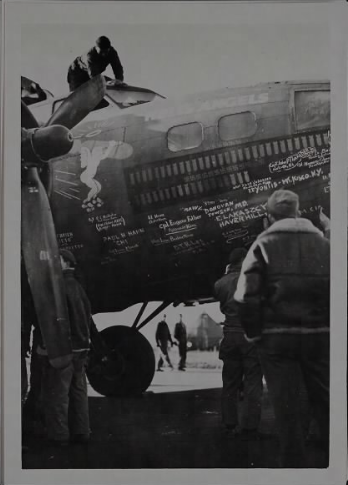

On the night of November 12, 1942, after hours of fighting off Japanese torpedo bombers, a Japanese destroyer launched a torpedo that struck Juneau on the port side. She began to list and retreated from the battle. Operating on one screw, the Juneau steamed towards Espiritu Santo for repairs. The following morning, a Japanese submarine fired another torpedo hitting Juneau in the same spot she was hit the night before. Following a loud explosion, the USS Juneau broke in two and sank in just 20 seconds. Concerned about the possibility of another submarine attack, the American task force left the scene. The USS Helena messaged a nearby B-17 search plane to report survivors in the water. Unfortunately, Helena’s message did not reach command headquarters, delaying rescue efforts for days. More than 100 men did survive the initial attack. Francis, Joseph and Madison Sullivan died instantly, but Albert may have survived until the second day before drowning. George lived for four or five days in a raft before succumbing, according to a letter from a shipmate to his parents. Eight days after sinking, ten survivors were plucked from the water. The tragedy claimed the lives of 687 men.

Back in Iowa, the Sullivan family received word that all five sons were missing. As a result of their deaths, the US War Department adopted the Sole Survivor Policy. This policy protected family members from the draft or combat duty if they already lost family members in military service. The parents of the Sullivan boys, Thomas and Alleta Sullivan, toured the country promoting war bonds and visiting shipyards and manufacturing plants to motivate workers. The only surviving Sullivan child, daughter Genevieve, 24, joined the WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service) and served for 21 months before being granted an honorable discharge. The US Navy later named two destroyers after the Sullivan brothers, and the Iowa Veterans Museum is named in their honor.

For 76 years, the wreckage of the USS Juneau rested undiscovered on the ocean floor. On March 17, 2018, an expedition funded by billionaire Paul Allen discovered the Juneau lying on her side about 2.6 miles below the surface of the ocean in the Solomon Islands. There are no plans to raise the ship.

If you would like to read multiple survivor accounts from the Juneau, or learn more about the Battle of Guadalcanal, search Fold3 today!