On October 1, 1942, the USS Grouper torpedoed the Lisbon Maru, a Japanese ship traveling through the South China Sea. Unbeknownst to US military officials, the Lisbon Maru was carrying 1,816 British prisoners of war captured after the Battle of Hong Kong in December 1941. The ship began to sink, and Japanese troops evacuated, but not before battening down the hatches and trapping the POWs below deck. The prisoners finally broke through the hatch covers and attempted to escape. More than 800, however, perished in the disaster.

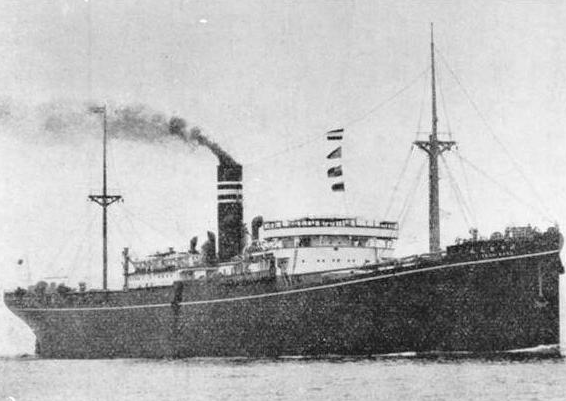

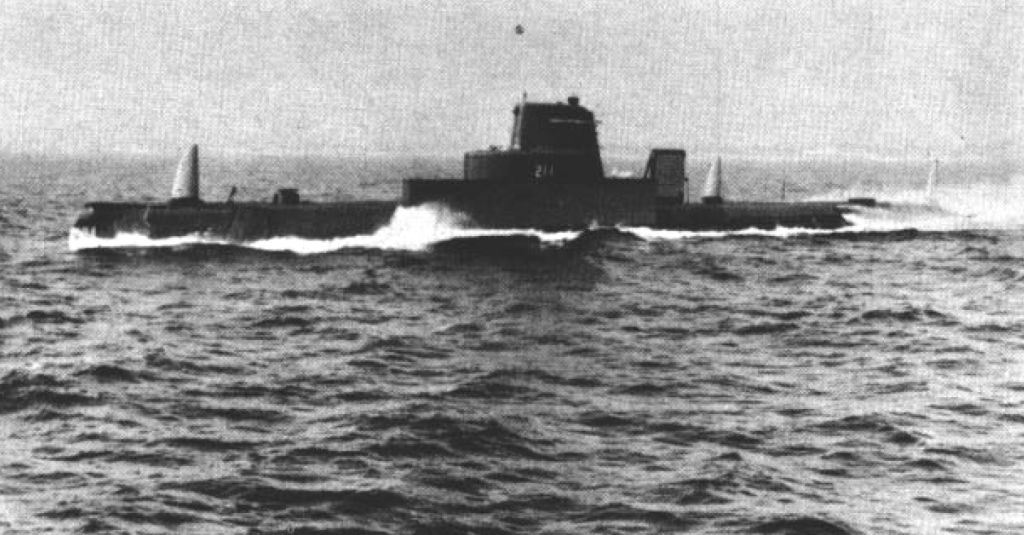

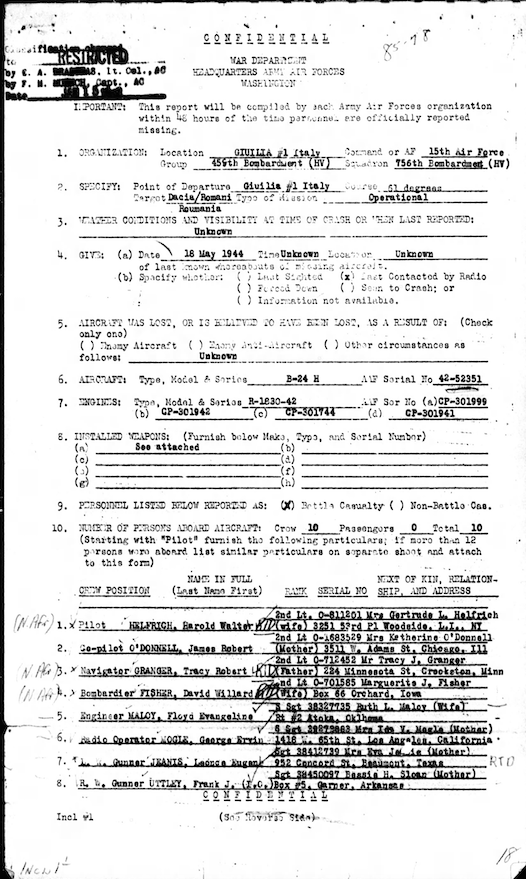

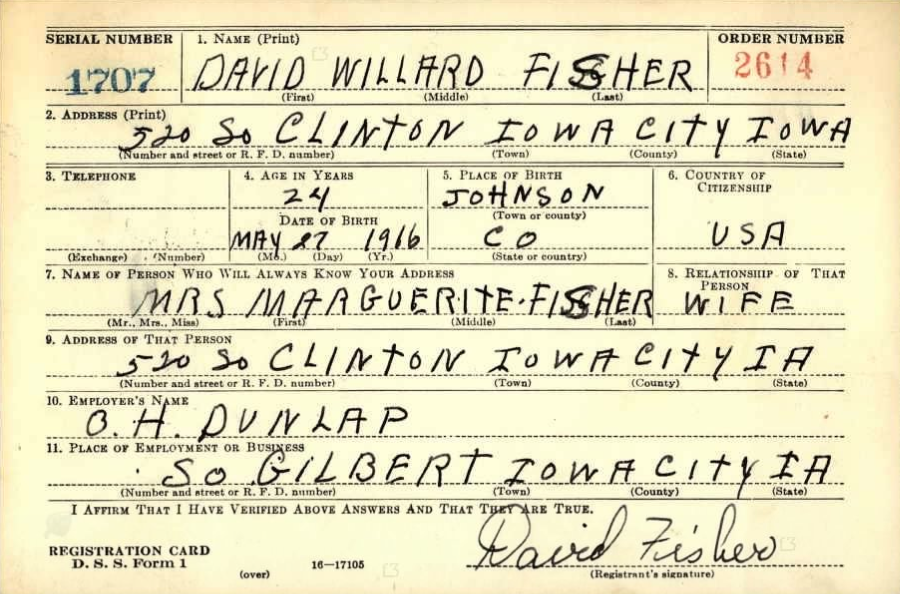

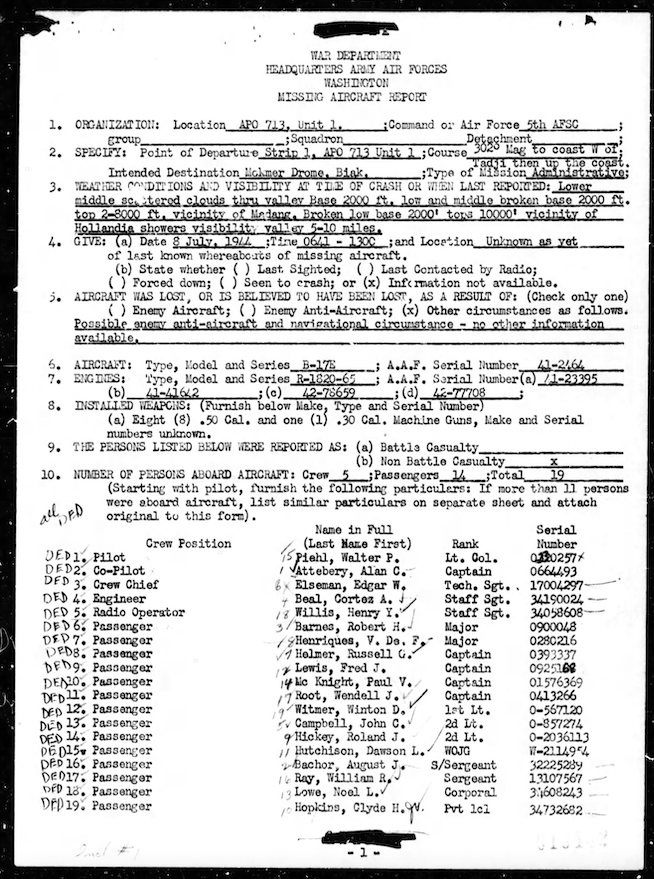

The USS Grouper was a Gato-class submarine and part of the Pacific Submarine Force in WWII. During her second patrol, the Grouper encountered the Lisbon Maru in the South China Sea. The 7,000-ton freighter turned armed troop ship was carrying some 800 Japanese troops and bore no flags or markings indicating that she also carried POWs. The prisoners had been captured at the Battle of Hong Kong, and many were sick and weak, having spent nearly a year in POW camps. They were being transported to provide slave labor to benefit Japan’s war effort.

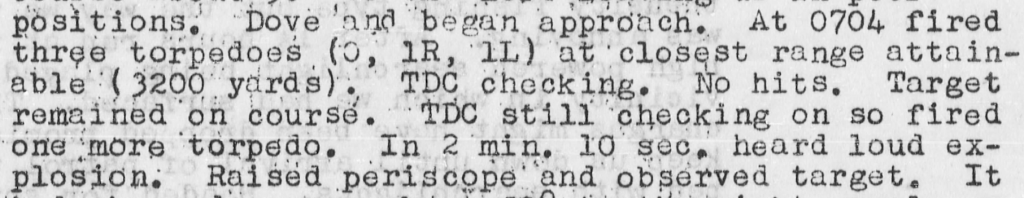

The Grouper tracked the ship in the early morning of October 1, 1942, but bright moonlight prevented a surface attack. Instead, the Grouper dove and waited for the right moment. Just after 7:00 a.m., the sub fired three torpedoes at the Lisbon Maru. They all missed, but a fourth torpedo collided with the ship’s engine room at the stern. The Grouper raised the periscope and noted that the vessel had stopped and was returning fire. At 8:45 a.m., the Grouper’s crew reported that Lisbon Maru was listing. They also recorded that an enemy plane flying overhead dropped depth charges. The sub cleared the area, still having no idea Allied POWs were aboard the ship.

On board the Lisbon Maru, the POWs were kept below deck, in dark, overcrowded, sweltering holds and without access to food or water. Throughout the day, the ship continued to list, and by the evening, Japanese troops began evacuating, leaving a small contingent of guards to prevent an escape.

Conditions below the deck were deteriorating. Exhausted prisoners tried desperately to keep the holds from filling with water using hand pumps. The following morning, the ship lurched, and water began pouring in. The POWs panicked and attempted to break through the hatches. Lt. Hargraves Milne Howell finally opened a hatch, and prisoners rushed to the deck. The remaining Japanese guards fired upon the first men to surface, but they were soon outnumbered. Prisoners jumped in the water, hoping to swim to a nearby island, but many drowned. Nearby Japanese boats refused to rescue prisoners flailing in the water and even fired upon them.

A contingent of Chinese fishermen risked their lives to rescue the POWs and bring them back to shore. However, Japanese soldiers soon recaptured them. At least 825 men died. Survivors were rounded up and transported to other POW camps, where many later perished. Lt. Howell was sent to Fukuoka POW camp, where he remained until his liberation on September 20, 1945. For his efforts to help free the POWs stuck below deck, he was awarded the MBE (The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire) for gallantry.

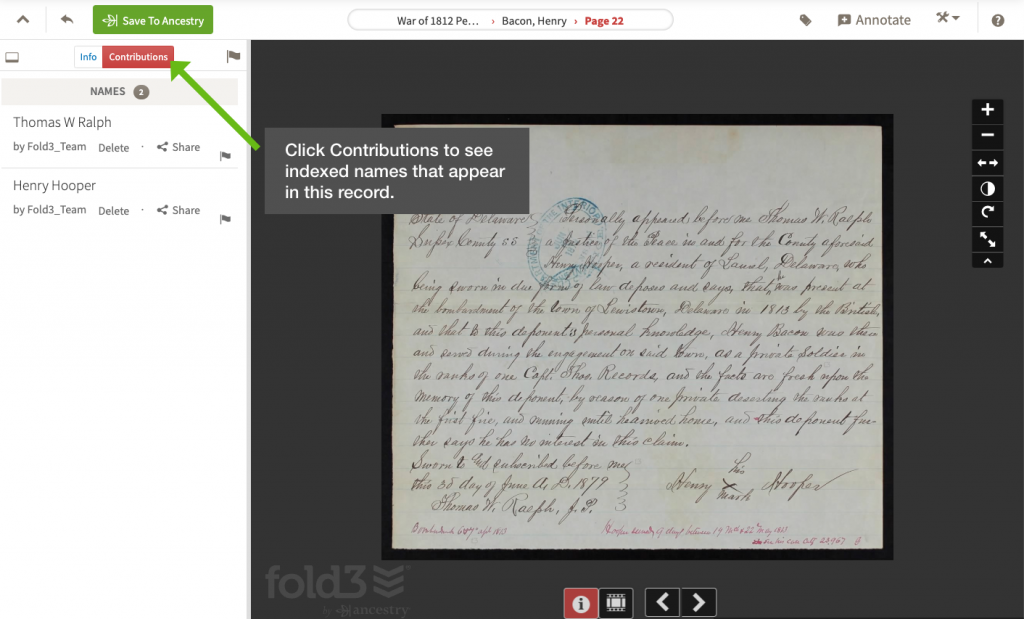

To learn more about the Lisbon Maru tragedy, search Fold3® today.