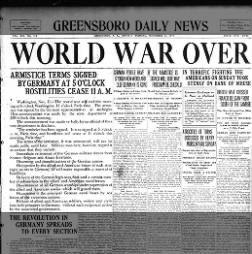

On November 11, 1918, at 11 a.m. the fighting of World War I finally ended as had been decided in an armistice signed by the Allies and Germany earlier that morning at 5 a.m.

Although Germany still held some Allied territory, its army and people were exhausted, starving, and losing hope. While Germany struggled to replace its fallen and deserting soldiers, the Allies were receiving American reinforcements at the rate of 10,000 a day. At home, unrest had broken out, and the Kaiser lost the confidence of the army, forcing him to abdicate on November 9. Added to that, Germany’s allies—Bulgaria, the Ottoman Empire, and Austria—had already signed armistices between the end of September and early November.

German representatives met with the commander in chief of the Allied armies, Ferdinand Foch, in a railcar about 40 miles northeast of Paris and signed the armistice on November 11. However, fighting between the two sides continued in some places between 5 a.m., when the armistice was signed, and 11 a.m., when the fighting was scheduled to stop.

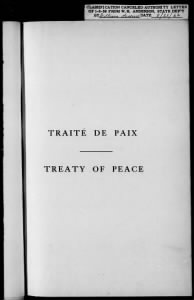

While the armistice ended the fighting, the war technically wouldn’t be over until Germany and its allies signed peace treaties. Representatives from dozens of countries (excluding Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and Bolshevik Russia) met beginning in January 1919 in Paris to formulate the treaties, though discussions were dominated by Britain, France, and the United States.

The Treaty of Versailles between the Allies and the Germans, signed June 28, required Germany to accept responsibility for the war and to pay reparations to the Allies. Germany also lost some of its territory and all of its overseas colonies and had to reduce the size of its navy and army. The German representatives had little choice but to sign the treaty, as the Allies were blockading German ports until a treaty was signed. Today, historians commonly agree that the terms and effects of the Treaty of Versailles sowed the seeds for World War II.

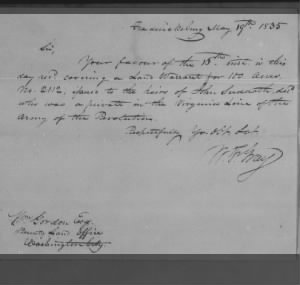

Did you have ancestors who fought in World War I? Tell us about it! To learn more about the conflict, you can also explore Fold3’s WWI titles, including newly added international titles from the United Kingdom and Australia.