Did you know that Fold3 has a huge number of documents from World War II about the Women’s Army Corps (WAC), including hundreds of photos? If you’re not already familiar with the WAC, you might be surprised to find out just how versatile this group was during the war.

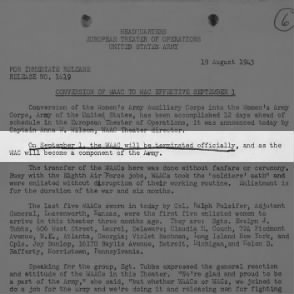

The WAC was originally formed as the WAAC (Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps) in 1942 as an auxiliary to the Army, but in 1943 it was incorporated into that military branch and renamed the WAC. The goal of the WAC was to free up men for WWII combat by replacing them with women in noncombatant military jobs. The women of the WAC (called WACs) worked with the Army in over 200 types of positions, including as clerks, stenographers, secretaries, teletype operators, mechanics, instructors, weather forecasters, course plotters, photo analysts, telephone operators, parachute riggers, drivers, radio operators, electricians, and cryptographers. However, within this diverse array of jobs, WACs were most often assigned to clerical and communications jobs, which the Army deemed appropriate for women.

Over the course  of the war, around 150,000 WACs served at home and abroad, in places like England, France, Italy, New Guinea, the South Pacific, North Africa, China, and India—just to name a few. Although they sometimes faced discrimination and criticism, WACs were in high demand, and the officers they worked with—including General Eisenhower—often praised them for their hard work and skill. Their admirable qualities were proven by the fact that at the end of the war, 657 WACs received citations and medals.

of the war, around 150,000 WACs served at home and abroad, in places like England, France, Italy, New Guinea, the South Pacific, North Africa, China, and India—just to name a few. Although they sometimes faced discrimination and criticism, WACs were in high demand, and the officers they worked with—including General Eisenhower—often praised them for their hard work and skill. Their admirable qualities were proven by the fact that at the end of the war, 657 WACs received citations and medals.

Do you have any family members who served in the WAAC or WAC? You can find all sorts of information and images from the Corps on Fold3.