One of Fold3’s newest titles is the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies. Like its name suggests, this collection contains the two navies’ official reports, orders, and correspondence from the Civil War. If you’re interested in the Civil War, this is the go-to title for contemporary, first-hand information about the Northern and Southern navies.

Originally compiled by the Navy Department, the Official Records of the Navies are organized into two series: Series I, with 27 individual volumes, and Series II, with 3 volumes and an index. Series I documents all wartime operations of the two navies, while Series II deals with statistical data of Union and Confederate ships, letters of marque and reprisal, Confederate departmental investigations, Navy and State department correspondence, proclamations and appointments of President Davis, and more.

It took about 40 years for the Navy Department to finish compiling the records, with work officially beginning in 1884 and the final volume of Series II being published in 1922 (and the index in 1927). Because of the massive number of pages contained in the Official Records, Fold3 is still working on getting all of it up on our site. At last check, the project was three-fourths complete (but at least you won’t have to wait 40 years!).

A few interesting finds in the Official Records of the Navies include the following:

- A Union account of the Battle of Gloucester Point, the earliest engagement between the Union navy and the Confederates

- A Confederate report on the Battle of Hampton Roads, the first battle of ironclad ships

- A letter from a lieutenant in the U.S. Navy detailing the death of a fellow lieutenant during the Second Battle of Fort Fisher, the battle in which the Confederacy lost its last seaport

Beyond historical information, the Official Records of the Navies can be a good place to look for any of your ancestors who served in either navy during the war. Take a look through the extensive 457-page index, and you’ll get an idea of just how many thousands of names are mentioned in the records. Even if you don’t find your specific ancestors, you’re almost guaranteed to find information about their commanding officers or the ships they served on, helping you to round out your general knowledge of what those ancestors’ lives were like.

Get started browsing through the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies here, or do a search instead.

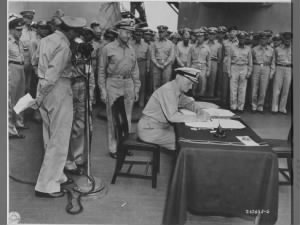

On September 2, 1945, Japan signed the Instrument of Surrender, officially ending World War II.

On September 2, 1945, Japan signed the Instrument of Surrender, officially ending World War II. After MacArthur finished, the

After MacArthur finished, the

When Hood was informed of the

When Hood was informed of the