In 1942, as Japanese forces advanced on Corregidor, soldiers from the US Army’s 31st Infantry Regiment burned the regimental battle standards and buried a silver bowl and cups. The bowl was a prized Army heirloom known as the Shanghai Bowl, and the soldiers didn’t want it to fall into enemy hands. When the war was over, a contingent, including one who helped bury the bowl, returned to Corregidor to retrieve it. It took two months of digging, but they eventually unearthed it. Today, the Shanghai Bowl remains a symbol of the heritage of the 31st Infantry Regiment and is housed at Fort Drum, New York.

In 1932, the 31st Infantry “Polar Bear” Regiment arrived in Shanghai. The Polar Bear nickname came from the regiment’s service in eastern Siberia during the Russian Revolution from 1918-1920. The regiment aimed to protect American citizens and property after hostilities erupted between Chinese and Japanese forces. While in Shanghai, officers of the 31st collected $1,600 in silver dollars and commissioned a Chinese silversmith to create a silver punch bowl and cups to commemorate the unit’s service. The bowl is 30 inches across by 21 inches deep and was used for special occasions, including ceremonies to commemorate the anniversary of the regiment’s founding.

The 31st kept the Shanghai Bowl at regimental headquarters overseas, so as WWII approached, it was in the Philippines. On the night of May 2, 1942, with enemy shells falling nearby, Capt. Earl R. Short led a small detail and buried the bowl and cups on a hillside on Corregidor. Shortly after, Corregidor fell to the Japanese on May 6, 1942, and Short was captured and taken POW.

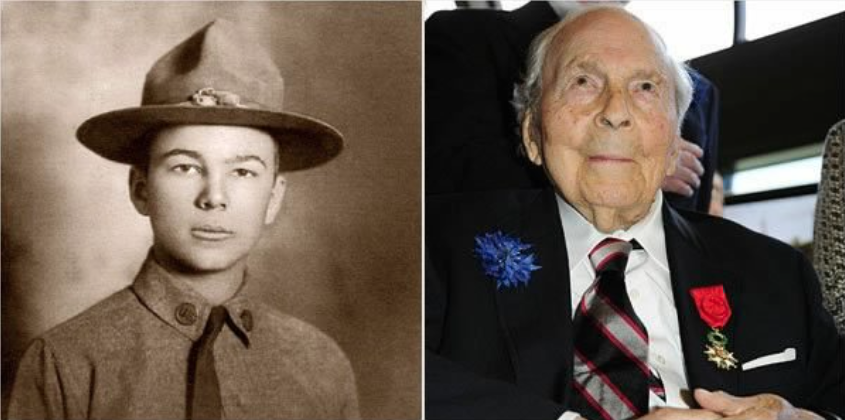

Some 1,600 soldiers from the 31st participated in the infamous Bataan Death March. They were already weakened and emaciated from four months of fierce fighting without replacements or resupply. Now, as POWs, they endured torture, starvation, and horrific conditions. More than 1,000 soldiers from the 31st Infantry Regiment died in captivity.

Following the war, Capt. Short (who was promoted to major after his release) went to Maj. Gen. Robert J. Marshall and told him about the buried bowl. Marshall ordered Short to find the bowl and sent a small detail of ten men with shovels to accompany him. After arriving at the hill where he’d buried the bowl, Short found the landscape transformed from heavy shelling. After a week of digging, he called for additional heavy equipment. After a two-month search, they finally found the Shanghai Bowl.

The Shanghai Bowl is still an important symbol for the US Army. The bowl remained with the regiment while they served in Korea, and after 55 years overseas, the Army transported the Shanghai Bowl back to the United States in 1987. Today, the Shanghai Bowl is a distinguished part of Fort Drum’s collection and is still brought out for special occasions.

If you would like to learn more about the Shanghai Bowl, or the 31st Infantry Regiment, search Fold3® today.