More than 3 million soldiers fought in the Civil War, and each had a story to tell. Some of those stories have been preserved through personal journals. We recently came across the journal of Union Soldier William Hosack. William spent nine grueling months as a POW, first at Libby Prison and later at Andersonville and Florence Prison. His journal is housed in Special Collections at Indiana University of Pennsylvania. Our special thanks to IUP for sharing William’s story with us.

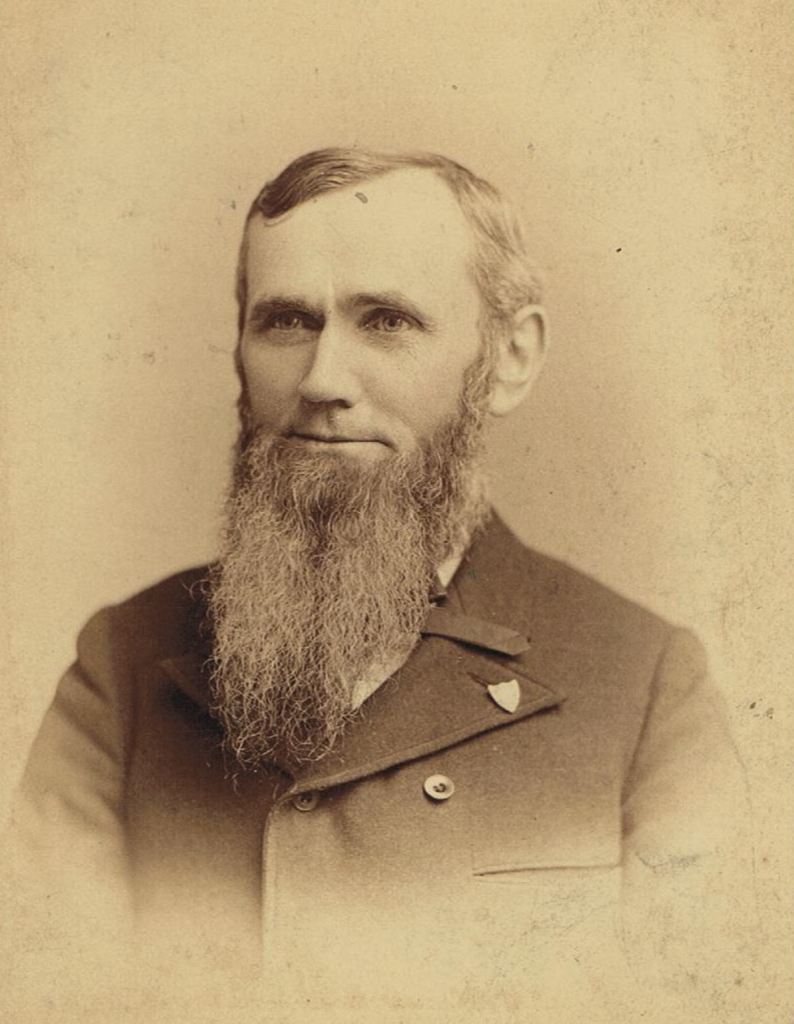

William Hosack was born on February 10, 1843, in Indiana County, Pennsylvania. His father Samuel died when he was just 6, so the seven Hosack siblings were farmed out to various family members and neighbors. William lived with his grandfather until age 17, then moved to the nearby town of New Alexandria to learn the blacksmith trade before enlisting in the Union Army.

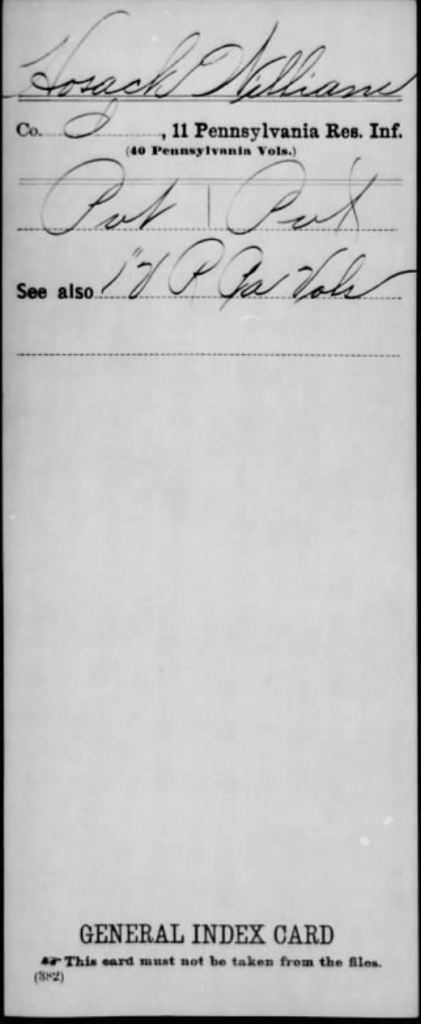

In 1861, William enlisted in the Pennsylvania 11th Reserve Infantry. He was just 18 and small in stature. Military officials refused to swear him in without the written consent of his mother, which he obtained. His first skirmish happened along the Potomac River near Washington, D.C. He was serving on picket duty and recalled that Union soldiers were on one side of the river and Confederate soldiers were on the other side.

“We were on friendly terms, and we met in the river and done trading until that Regiment was relieved by a South Carolina Regiment. The next morning as some of our men went to wash as usual, a comrade of Co. G was shot in the leg which was a signal for hostilities when a lively skirmish opened.”

During 1862, William’s Regiment fought in fierce battles, including the 2nd Battle of Bull Run, South Mountain, and Antietam. After Antietam, William said they returned to camp near Sharpsburg, “blanketless, shoeless, no money and with tattered uniforms.” He described a brutal winter with conditions that tried the endurance of the men. The following summer William’s regiment marched towards Gettysburg, arriving July 2, 1863. They fought on Little Round Top, and William poured volleys of buckshot upon the enemy, then charged them with his bayonet. He recollected that one of the last shots of Gettysburg was fired at him.

“Next morning at break of day – being the 4th of July – I got up cold, saw a blanket over the stone fence, I put it around me as was walking my beat when a rebel picket shot at me which was one of the last shots of the battle, as all the rebels army had retreated in the night and the picket line was last to leave and gave me a parting shot. I heard the ball pass my head.”

During the Battle of the Wilderness, in May 1864, William was shot in the heel of his shoe. Despite all the hardships he had endured thus far in the war, it did not compare to what was shortly to come. On May 30th, during the Battle of Bethesda Church, William was captured and taken prisoner. For the next nine months, he endured hunger, sickness, and every kind of deprivation before being liberated in March 1865. William was first taken to Libby Prison where his blanket and tent were confiscated. The guards demanded that prisoners turn over any money and searched each prisoner.

“I had seven dollars in green backs which I slipped in a hole in the sleeve of my comrade’s blouse. He was searched before me, and they failed to find the money. Then I was searched. I had $2.00 in their money, but they would not take that.”

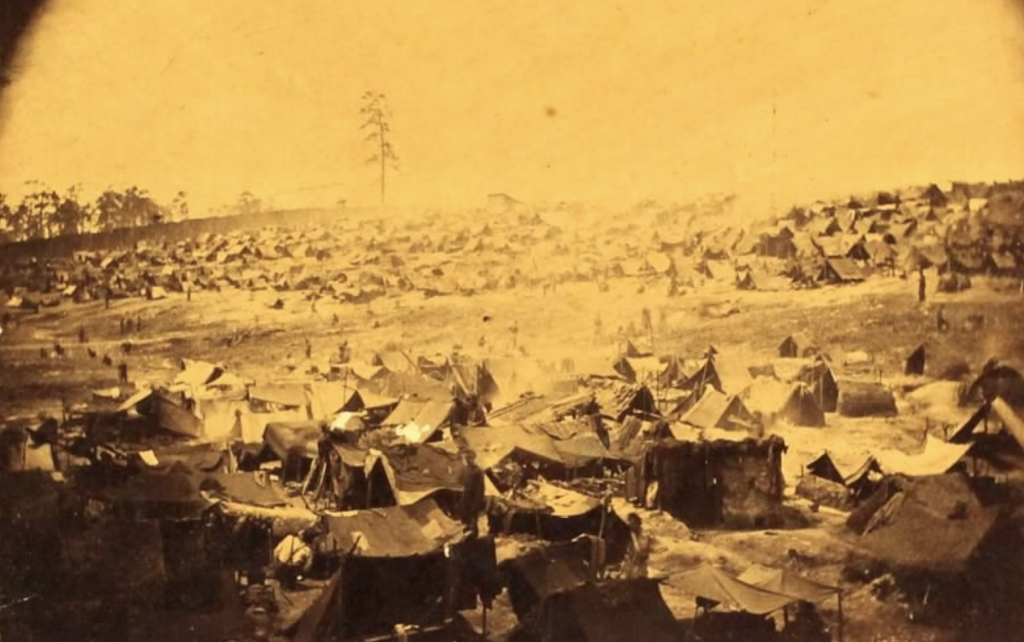

William staked out a small space on the floor at Libby Prison and used his shoes as a pillow at night. He spent 11 days there before being transferred to Andersonville. The sights, sounds, and smells at Andersonville were shocking. Some prisoners had small tents, others had blankets that hung over a pole, but thousands had nothing and lay exposed on the bare ground.

“The suffering there was horrible from hunger and disease, starvation and death. The filth I will not attempt to describe. It is a miracle that we didn’t all die.”

A small, filthy stream ran through the center of the camp. As it was the only source of water, prisoners were forced to drink from it. Some started to dig wells, in hopes of reaching clean water. Other prisoners realized that escape might be possible by digging tunnels instead of wells. A few did escape, so guards forced them to fill in the wells. Prisoners survived on meager food rations which usually consisted of mush or boiled rice and cornbread, equaling about a pint of food a day. The deprivation brought out the worst in some.

“Some of our prisoners were very bad men, they went by the name of “Raiders”, would steal and murder for money. The prisoners formed a police force and arrested a bunch of raiders and organized a court as many prisoners were lawyers – and tried these men and convicted six of murder and were sentenced to be hung. I saw them drop, all at the same time. One man’s rope broke and he fell to the ground, but another rope was gotten and hung him again. It was a sad sight.”

Andersonville was extremely overcrowded. Prisoner deaths would average 100 per day. Scurvy caused much suffering and prisoners were covered with infected sores. William recalls that many just sat in the hot sun until relieved by death.

“Each morning a wagon was brought in to gather up the dead, the bodies were thrown on like that much wood until the load was full then taken to the cemetery and continued until all were gathered up.”

In October 1864, some prisoners including William were transferred to Florence Prison in South Carolina. William could hear bombs exploding in Charleston and recalled that prisoners cheered after each explosion. Winter was approaching and temperatures were dropping. William spent a cold winter sleeping on bare ground that was sometimes frozen. In December 1864, word spread that a big prisoner exchange was coming. William was sure he would be exchanged – but he wasn’t chosen.

“The gate was closed which was great disappointment to me, yet I determined to live it through if possible. Done all I could and prayed to God to help me. And he did help me.”

That help came in the form of sweet potatoes. William and a fellow prisoner traded a gold pen for 1 ½ bushels of sweet potatoes. They boiled the potatoes and ate a few, relishing each bite. He then sold the rest and earned a dollar. About this time, he was detailed to go outside the prison walls to build a smallpox hospital. On the outside, he took the dollar and purchased additional foodstuffs, allowing the prisoners to make a stew using cuts of meat nobody wanted, like cow stomach.

“I washed it the best I could, then cut it up in squares and boiled it until evening, then we tried to eat it. We could not masticate it, but we chewed it a while then swallowed it and the stomach done the rest. We never drew meat, except in Andersonville, for a time we drew spoiled bacon. Possibly they thought it good enough for the yanks.”

The food saved the lives of prisoners, who were on the verge of starvation. They were willing to eat anything. William recalled seeing prisoners pull the head of a dog out of a filthy swamp and roast it over the fire to pick off small pieces of meat.

William was determined to survive. He often thought of his widowed mother, and it gave him the incentive to keep going. He looked forward to reuniting with his family. Finally, in 1865, William was freed in a prisoner exchange. He was carried to a ship and transported to Annapolis, Maryland, where he was hospitalized. When sufficiently recuperated, William started for home and the reunion he had dreamed about.

“I arrived home at Blairsville and rapped on my mother’s back door and my sister was about to open the door, I opened it for myself. For a few moments mother nor sister knew me. Finally sister said it is “Will”. I need to say nothing more, you can imagine the rest.”

William Hosack went on to become a husband and father. He studied medicine and became a respected doctor. To learn more about the Civil War and the soldiers who fought in it, visit our Civil War collection on Fold3®.