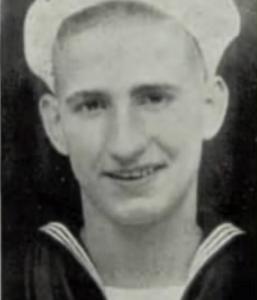

On April 1, 2022, the National Archives and Records Administration will release the 1950 U.S. Census to the public. These records may provide new insights into the 16 million American men and women who fought during WWII. More than 400,000 Americans died during the war. As a result, many will find ancestors enumerated in the 1940 U.S. Census but no longer living in 1950.

Soldiers returning from WWII arrived home to sweeping new legislation known as the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act, or G.I. Bill. The G.I. Bill provided benefits to returning veterans, including money for education, job training, and low-interest home loans. As a result, almost half of college admissions in 1947 were veterans. With so many veterans attending college, it’s important to note that in the 1950 U.S. Census, college students were enumerated where they attended school and not where their family was living.

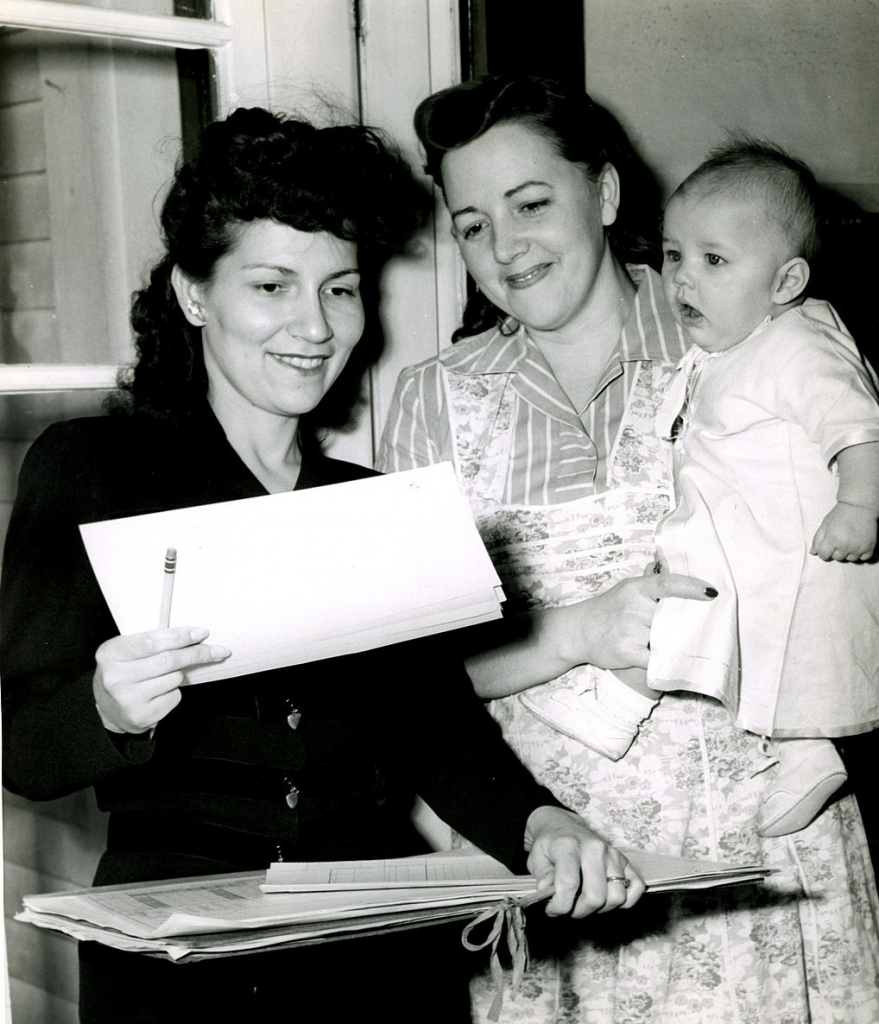

Returning soldiers also started families, ushering in the “baby boom.” The 1950 U.S. Census will show veterans all over the country listed as homeowners. Many took advantage of the low-interest loans to purchase homes, and new neighborhoods of mass-produced subdivisions sprang up all over the country. By 1950, veterans had become the largest single group of homeowners and helped usher in an era of middle-class prosperity.

Some other veteran-related things to watch for in the 1950 U.S. Census records are:

- The 1940 standard census forms had lines for 40 persons. In 1950, this number was reduced to 30 lines, allowing enumerators space to take notes on additional sample questions answered by every fifth person. Men on these “sample” lines were asked if they served in the military during WWI or WWII or any other service, including the present.

- Military and civilian personnel living at Canton, Johnston, Midway, and Wake Islands were enumerated and will be included in the 1950 U.S. Census release records.

- Enumerators were instructed not to enumerate Americans, including soldiers, sailors, marines, and airmen who worked for the United States Government while living abroad in 1950. They only enumerated those living in their enumeration district.

- The names and rank of a few U.S. military personnel overseas are included in correspondence in Binder 36-C, Members of Armed Forces and U.S. Citizens Abroad, available here from the National Archives.

- Officers and crews of U.S. flagged vessels are likely found in an enumeration district in either the vessel’s home port or where the vessel was on April 1, 1950 (the official census day).

- Those serving in the Coast Guard, including vessels, lighthouses, and other stations of various kinds, were enumerated. Often the lighthouse or vessel was its own enumeration district. Commanding officers of Coast Guard vessels received forms for each of their crew. If someone was away on leave or absent on temporary duty, their commanding officer filled out the form as much as possible. USCG uniformed and civilian personnel living in “barrack-type” quarters received a Form P2, Individual Census Report, which they filled out. A regular census enumerator visited USCG personnel who lived either on-base or off-base with their dependents.

Using new, proprietary Artificial Intelligence (AI) handwriting recognition technology, Ancestry® announced that it will deliver a searchable index of the 1950 Census faster than ever before. Volunteers will evaluate census extraction records to ensure accurate results. We anticipate the 1950 U.S. Census will be fully indexed and available to search online this summer.

Keep an eye out for the 1950 U.S. Census records coming to Ancestry®, and search Fold3® today to learn more about your veteran’s military history.