Do you have an ancestor who served in the War of 1812? The digitization of the War of 1812 pension files continues and is now 86% complete. If you find your ancestor’s pension file, here are some tips on using these amazing records to research your military ancestors.

Find the Pension File: From the War of 1812 Pension Files publication page, enter a soldier’s name in the search box OR select Browse to search for files by state. Remember that many War of 1812 veterans received bounty land, so the state where your ancestor died may not be the state from which he served. Try a variety of search parameters until you locate the correct pension file.

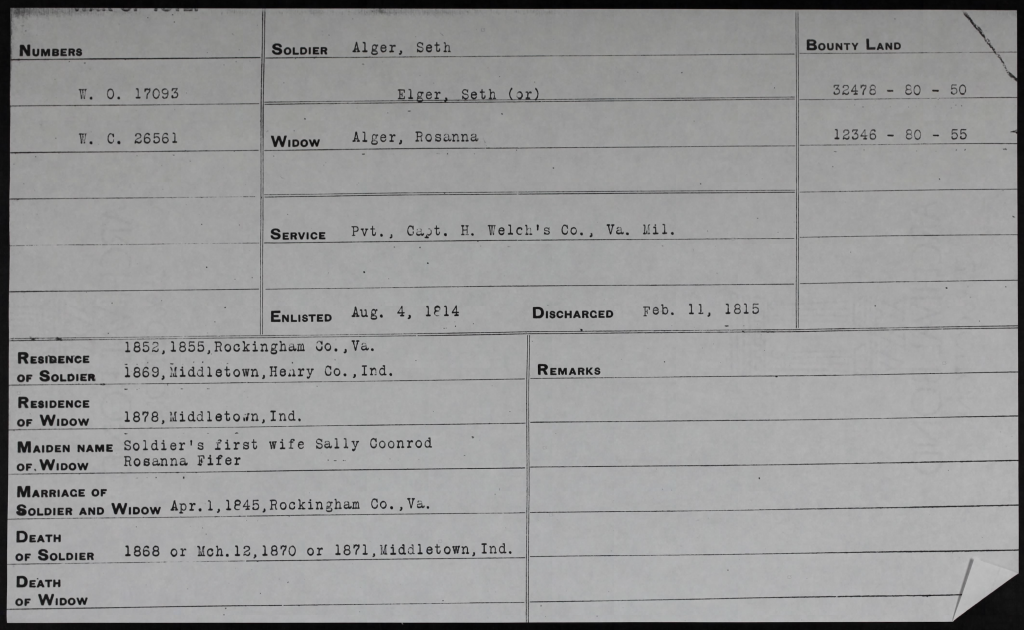

The First Page: The file’s first page contains a summary and may include many details.

Spelling Variations for the Soldier’s Name: This pension file shows that the soldier’s records might be found under two different spellings (Alger or Elger). However, as we dive deeper into the manuscripts in this file, a third spelling is also used (Alaer). These are all great clues for further research.

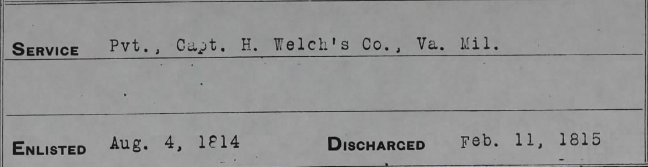

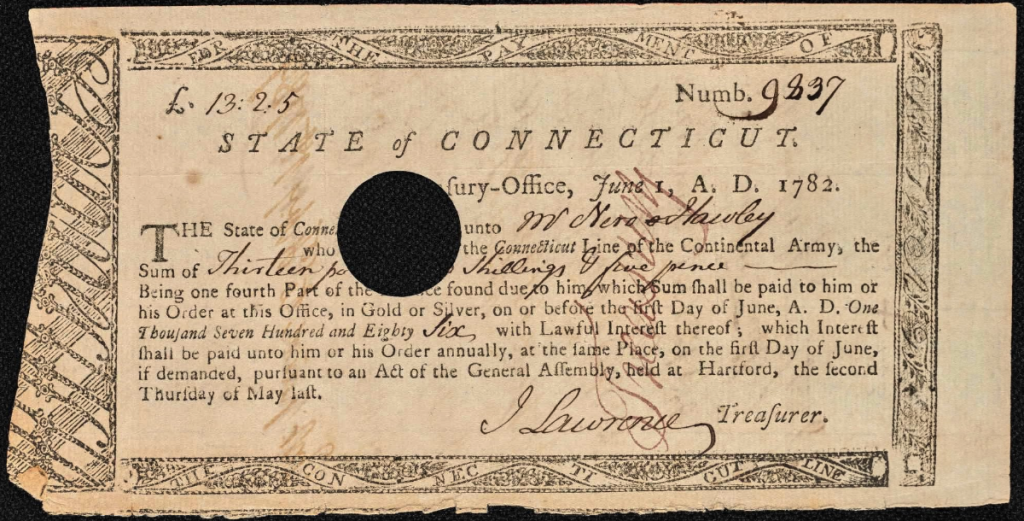

Where the Soldier Served/Enlistment and Discharge Dates: After learning which regiment your ancestor served in, you can do further research on that regiment. Which battles did they participate in? Who commanded the regiment? Sometimes, pension files give details about the regiment’s service, but if your ancestor’s file doesn’t contain those details, search the commanding officer’s pension file or the files of others who served in the same regiment. These can all help build the narrative of your ancestor’s service.

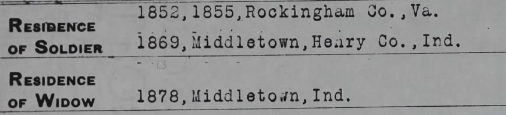

The Veteran’s Residence: Knowing where our ancestors lived is crucial to finding additional records. This pension file shows that the soldier relocated from Virginia to Indiana and that, by 1878, he had passed away, but his widow survived him. Sometimes, these boxes are left blank on the first page, but take the time to read through the manuscripts in the pension file, and you will likely learn more about the soldier’s residence.

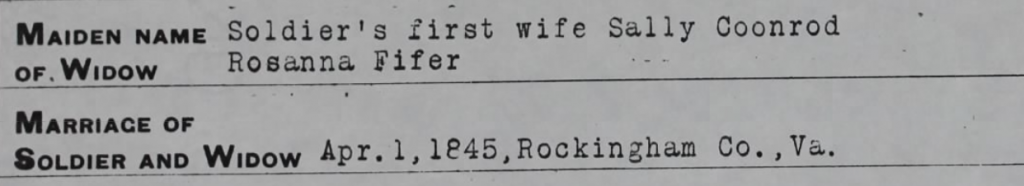

The Widow’s Maiden Name and Marriage Date: In the example below, we are lucky to find this information right on the first page. Often, it requires reading through the file very carefully. Researching women can be particularly difficult, so learning that this soldier was married twice and that the file contains the maiden names of both women is extremely valuable. A widow had to prove her marriage to the veteran, so you may find an affidavit from the person who performed or witnessed the marriage. We have even come across pages from the family bible in the pension file as proof of marriage.

Did the Widow Apply for a Pension: When a veteran’s widow applied for a pension, officials created a file and gave it a number. W.O. refers to the Widow’s Original. When the application was granted, it became known as the W.C. or Widow’s Certificate.

Did the Soldier Receive Bounty Land: Various acts of Congress granted bounty land for soldiers who fought in the War of 1812. This pension file reveals that this veteran received 80 acres of bounty land in 1850 (Certificate No. 32478) and 80 acres of bounty land in 1855 (Certificate No. 12346).

Affidavits: Proper military records were not kept during the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812. Consequently, soldiers had to provide proof of their service. Pension files contain affidavits of individuals who hope to provide that proof. The affidavits may be from fellow soldiers, acquaintances, family members, etc. These are written in quill and ink and may be difficult to read, but they can reveal amazing details. Take advantage of Fold3’s® Viewer Tools along the right margin to enlarge, rotate, and adjust the contrast to make these manuscripts easier to read. You can also transcribe these records using the ‘Annotate’ feature and then select ‘Transcription.’

Children and Dependents: Pension files may contain the names and birthdates of the veteran’s children.

Death Date of the Soldier: Pension files usually contain the death date of the veteran.

Use these helpful tips and dive into our War of 1812 Pension Files to learn more about your ancestors’ military service. Search the free War of 1812 Pension Files collection today on Fold3®.