In late October 1861, more than 80 ships carrying US sailors and soldiers set sail from Hampton Roads, Virginia, for Beaufort, South Carolina. The mission was dubbed the Great Expedition, and it was in response to President Lincoln’s call for a blockade of Confederate ports in the South. The newly formed South Atlantic Blockading Squadron hoped to develop a base at the Port Royal Sound in South Carolina. Unbeknownst to Navy officers, the armada was heading straight into the path of a hurricane. Before the Battle of Port Royal began one week later, Union soldiers and sailors fought for their lives in a battle against Mother Nature. Some did not survive.

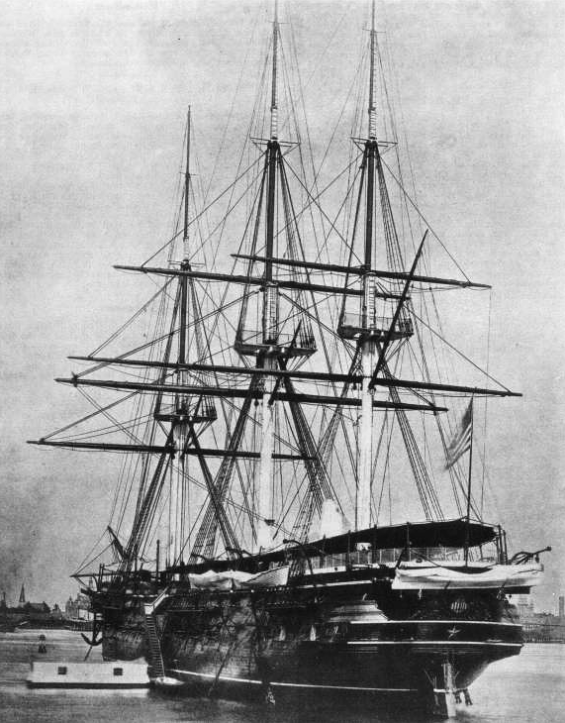

On October 29, 1861, the Naval fleet assembled at Hampton Roads. They set sail arranged in three parallel lines, each following another at about a half-mile distance. The USS Wabash took the lead as flagship.

The Expedition enjoyed calm seas and light winds for the first few days. However, a tropical storm churning off the tip of Florida was climbing the eastern seaboard and had developed into a hurricane.

On November 1, while rounding Cape Hatteras, the winds intensified and increased to a gale. Heavy seas caused the orderly columns of ships to disassemble, and the fleet scattered. One sailor aboard the Wabash described water crashing over the gunboats and side-wheel steamers lurching so ferociously that their paddles revolved in the air. Throughout the night, timbers creaked and groaned as the ships rolled and pitched in the storm.

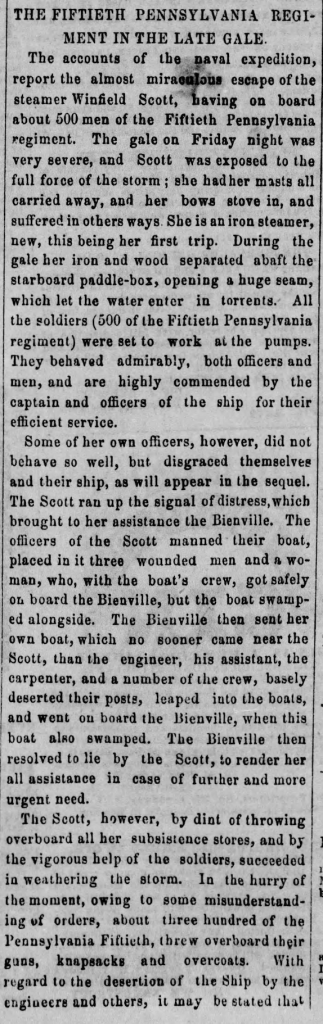

Onboard the steamer Winfield Scott, 500 soldiers from the 50th Pennsylvania fought to keep the ship afloat as waves battered it. The masts broke, and a huge seam opened onboard the vessel, allowing torrents of ocean water to spill in. The soldiers worked feverishly to pump out the water, throwing anything with extra weight overboard, including their guns, knapsacks, and overcoats.

Another ship, the Bienville, tried to come to the rescue, but the engineer and several crew members from the Winfield Scott abandoned their posts and leaped into the rescue boat, which was then swamped. Miraculously, the Winfield Scott survived the storm and was towed to safety by the steamer Vanderbilt.

The SS Governor sank during the storm, but in a daring rescue by the USS Isaac Smith and the USS Sabine, all but seven of the nearly 700 men were saved before the ship went down.

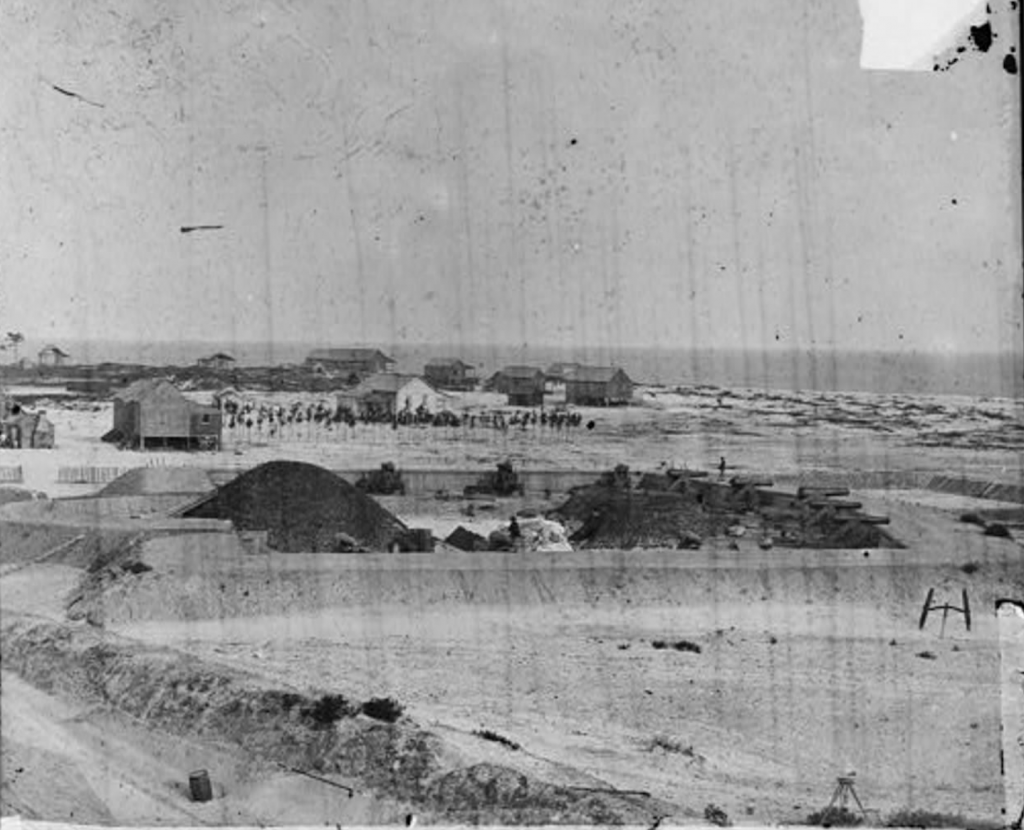

On November 4, the battered ships began to assemble outside the Port Royal Sound. On November 7, the Battle of Port Royal began, and despite its weather-worn fleet, Union forces took control of Fort Walker and Fort Beauregard, and Confederate forces retreated. Union forces then established a base of operations to support the Union blockade of Confederate ports.

If you would like to learn more about the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron or the Battle of Port Royal, search Fold3® today.