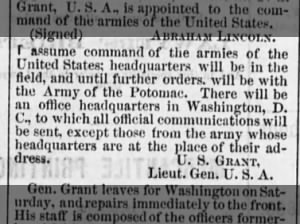

On March 9, 1864, Ulysses S. Grant was promoted to lieutenant general and made general-in-chief of the Union armies. In this position, Grant would ultimately prove the general most responsible for the Union victory in the Civil War.

After the outbreak of the Civil War, Grant—who had previously served in the army—rejoined as the colonel of an Illinois volunteer regiment. He received steady promotions until attaining the rank of major general (in the regular army) in command of the Military Division of Mississippi. Meanwhile, he had likewise been gaining recognition for his capture of Forts Henry and Donelson and victories at Vicksburg, Chattanooga, and others.

Grant’s successes led to the introduction of legislation in Congress to revive the rank of lieutenant general (last held by George Washington) so that Grant could be awarded that rank and thus gain command of the entire Union Army. President Lincoln, who had never met Grant but was unhappy with the performance of the previous commanding generals, also threw his weight behind the bill, and it passed and was signed into law in late February 1864.

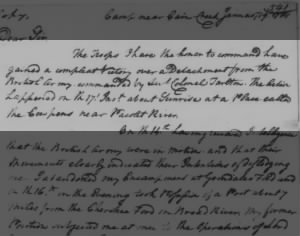

Grant’s name was shortly thereafter submitted to the Senate for confirmation and his commission was signed by the president. Grant was in Tennessee when he received word of his pending promotion to lieutenant general, and he traveled to Washington DC in early March to accept his new commission. He met President Lincoln for the first time on the 8th at a reception at the White House, and then the following day, March 9th, he returned to the White House for an acceptance ceremony.

President Lincoln wanted a commanding general who would take initiative and responsibility and act independently, freeing Lincoln from having to make military decisions. Grant was happy to oblige. He quickly put his senior command in place and set his basic strategy. Rather than commanding from the capital, Grant decided he would command from the field—attaching his headquarters to the Army of the Potomac—and commenced a course of action based on attrition.

Though Grant’s path to victory was far from easy—and his detractors would accuse him of being a butcher for his heavy casualties—he successfully destroyed the Confederates’ ability to fight and kept their armies on the defensive, ensuring the eventual success of Union forces and the preservation of a unified nation.

Learn more about Ulysses S. Grant by searching Fold3.