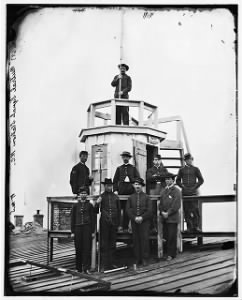

In this month of both Veterans Day and Thanksgiving, take a moment to visit the two interactive memorial walls on Fold3—the USS Arizona Memorial and the Vietnam Veterans Memorial—to pay tribute to America’s fallen heroes who perished in the attack on Pearl Harbor or during the Vietnam War. These interactive memorials allow you to learn more about the people whose names are inscribed on the walls as well as share your own facts, stories, and photos in remembrance of the veterans.

Interactive USS Arizona Memorial

When the Japanese bombed the U.S. Pacific fleet at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the USS Arizona was sunk, killing 1,177 officers and crew. The USS Arizona Memorial was built in 1962 over the ship’s wreckage to honor the Arizona’s casualties and commemorate the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Fold3’s Interactive USS Arizona Memorial includes a high-resolution image of the wall that you can search or browse to find the names of servicemen who died on the Arizona. Each name is linked to an Honor Wall page where you can find information about the veteran as well as add your own photos or tributes.

Interactive Vietnam Veterans Memorial

The Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington DC was completed in 1982 and is etched with the names of more than 58,000 veterans killed or missing during the war. The interactive memorial on Fold3 was made of 6,301 photographs of the physical wall that were stitched together by computer into a single, high-quality image.

As with the Interactive USS Arizona Memorial, the Interactive Vietnam Veterans Memorial allows you to either search for a name or look at a high-resolution image of the wall—as if you were really in Washington DC. Like the interactive Arizona memorial, every name on Fold3’s Vietnam wall is connected to an Honor Wall page for the veteran that you can view or edit.

If you haven’t visited these interactive memorials before, take a moment to do so and perhaps leave a tribute for veterans in your family whose names are on the walls. Or leave a tribute for any veteran, no matter what time period they served, by expanding or creating a memorial page for them on Fold3’s Honor Wall.