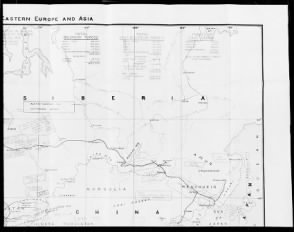

On September 4, 1918, American troops landed in Archangel, northern Russia, as part of an Allied intervention toward the end of World War I; American forces were also sent to Murmansk, near Finland, and to Vladivostok, in eastern Siberia.

Following a Bolshevik takeover of the Russian government in October 1917, Russia signed a peace treaty with the Central Powers in March 1918. With Russia no longer fighting with the Allies, the Eastern Front collapsed, allowing Germany to send troops that had previously been committed in the east to the Western Front, which the Allies were desperate to prevent.

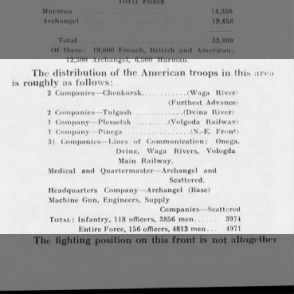

So in the summer of 1918, the Allies sent thousands of troops to Russia, including 5,000 Americans to northern Russia and 8,000 Americans to eastern Siberia. They were tasked with reopening the Eastern Front, which they would try to accomplish by aiding anti-Bolshevik Russian forces (and the Czech Legion, 60,000 former Czech prisoners of war) who were willing to fight against the Central Powers. The troops were also meant to prevent stockpiles of unused supplies the Allies had previously sent to Russia from falling into German or Bolshevik hands.

However, just a few months after the Allied arrival, World War I ended. Despite this, the Allied troops were kept in Russia even though there was no longer a need for a new Eastern Front. Their mission became more nebulous, compounded by the individual allies’ varying motives and priorities.

Morale dwindled among American and other Allied troops stationed in northern Russia, especially after the WWI armistice in November. They often didn’t understand why they had been sent to Russia in the first place, let alone why they were still there when the war was over. As they became increasingly discontent, some Allied forces refused to follow orders, and several mutinies occurred. Finally, in summer 1919, the Americans in north Russia were pulled out, and in April 1920 the last of the American intervention forces were withdrawn from Siberia.

Did you have any relatives involved in the Allied intervention in Russia? Tell us about it! Or you can learn more about the intervention in the collections “US Expeditionary Force, North Russia” and “WWI Supreme War Council” on Fold3.