In November 1942, an air transport crew ferrying a B-17 Flying Fortress to England diverted to Greenland to participate in a search for an overdue plane. During the search, the Flying Fortress crashed on the Greenland ice cap. Before the epic ordeal was over, five men died (including three rescuers), and the others spent months on the ice before being rescued the following Spring.

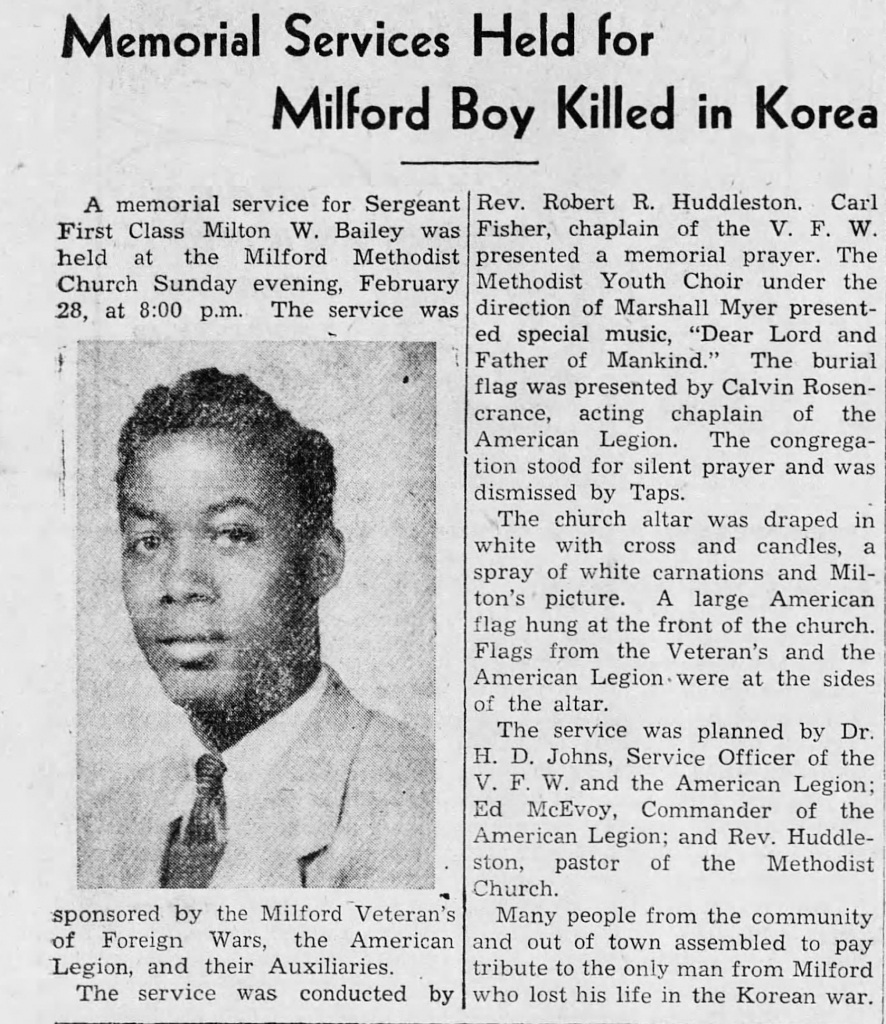

On November 6, 1942, pilot Lt. Armand L. Monteverde, co-pilot Harry E. Spencer, and navigator William F. O’Hara, along with their crew, were flying near Greenland when military officials asked them to divert and assist in a search for a missing aircraft. The aviators landed in Greenland. Foul weather made the search difficult and often grounded the crew. On November 9, the clouds broke, and the crew, including Sgt. Paul J. Spina, Pvt. Alexander F. Tucciarone, Corp. Loren E. Howarth, and Pvt. Clarence Wedel took off for another search. Sgt. Alfred C. Best and S/Sgt. Lloyd Puryear came along to help.

Heavy cloud cover moved in during the flight, and the line between sky and land became indiscernible. Suddenly, the plane lurched. A wingtip had brushed the ground. Before the pilot could react, the plane crashed violently and skidded, and the fuselage broke apart. Crew members were battered and bruised but survived. The most seriously injured was Spina, who broke his wrist and was thrown from the plane.

The men huddled together in the fuselage for warmth. The extreme cold and biting wind made the situation miserable. After a few days, the weather eased up, and crew members ventured out to assess the situation. After taking a few steps, Spencer fell 100 feet into a deep crevasse. Fortunately, an ice block wedged in the gap stopped his fall. Fellow crew members used a parachute harness and rope to hoist him to the surface, but the men soon realized they were surrounded by deep crevasses that threatened to swallow the plane. O’Hara also suffered from frostbite, having gotten snow in his boots while helping Spina and Spencer.

After six long days, Howarth got the smashed radio working and sent an SOS message. Back at the base, rescuers worked frantically to develop a plan. In the meantime, they dropped supplies when the weather allowed.

Over the next five months, rescuers tried repeatedly to reach the men with multiple attempts using dog teams, motor sleds (a type of snowmobile), and aircraft. Extreme weather and the dangerous crevasses made conditions treacherous. During one rescue attempt, a plane managed to land on the ice and picked up Tucciarone and Puryear. They were flown to safety, but while attempting to rescue Corp. Howarth, the plane went down, killing both crew members and Howarth. Another failed attempt took the life of a rescuer, Lt. Max Demorest, who died after he drove his sled into a deep crevasse.

About one month into the ordeal, six men remained at the crash site. A seventh man, rescuer S/Sgt. Don T. Tetley joined them after reaching the site on a sled. O’Hara’s feet were in bad shape, so Tetley, Spencer, and Wedel loaded O’Hara on a sled and decided to try to make it to the base. As they were crossing the ice, Wedel suddenly broke through and disappeared. He had fallen through a shallow ice bridge over a deep crevasse. The ice had claimed another victim.

The sled’s motor failed a short time later, leaving the men stranded. To make matters worse, O’Hara had developed gangrene in his feet. Rescuers kept both groups resupplied with airdrops when the weather allowed. The men at the sled camp built a snow fort, and the driving snow made further rescue attempts impossible until February.

When the weather cleared in February, rescuers landed a pontoon plane on the snow and picked up Tetley, Spencer, and O’Hara. It had been three months, but the men were now safe. All three were hospitalized, and O’Hara had to have both feet amputated. The focus now became the men back in the wreckage.

The glacier was moving at the wreck site, and the plane was slowly slipping into a crevasse. Rescuers decided to land another aircraft at the sled camp, where they would use a dog team to make their way to the wreckage. In late March, rescuers reached the site. The men had been on the glacier for five months. They were taken back to the sled camp and loaded in a pontoon plane. On April 6, 1943, the plane successfully took off from the ice field. With most of their fuel spent, the aircraft made a safe belly landing back at the base.

On May 4, 1943, newspapers across the country published the heroic story of survival. Three of the survivors, Monteverde, Spencer, and Tetley, were invited to the White House to meet President Roosevelt. If you would like to learn more about this incident and the heroic survivors, search Fold3® today.