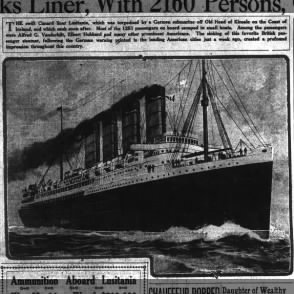

On May 7, 1915, the British passenger liner RMS Lusitania was torpedoed and sunk by a German submarine off the coast of Ireland, killing 1,198 passengers and crew and sparking outrage on both sides of the Atlantic.

When the Lusitania set out on its final voyage on May 1, World War I had been raging for almost a year (though America was still neutral), and Germany had begun unrestricted submarine warfare around the British Isles. Still, despite a warning placed in newspapers by the German embassy that anyone traveling on a British or Allied ship did so at their own risk, many felt that the Germans would never sink a ship with so many civilians and that the Lusitania was much too fast for a submarine to catch anyway. So the Lusitania left New York, headed toward Liverpool, with about 2,000 passengers and crew—and munitions intended for the British war effort—on board.

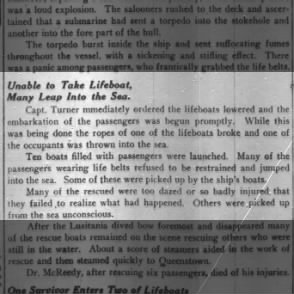

The Lusitania’s crossing was uneventful, though as the ship neared Britain it received a few general warnings about German submarines operating nearby. Then, at 2:10 p.m. on the 7th, only 11 miles off the coast of Ireland, the ship was struck by a torpedo fired by a German submarine, U-20. The torpedo hit amidships on the starboard side and was quickly followed by a secondary explosion (the cause of which remains a mystery today, though there are many theories). As water rushed into the lower portion of the Lusitania, the ship began to list severely.

Though there were enough lifeboats and lifejackets for everyone, the ship sank far too rapidly (in just 18 minutes) for most people to make use of them. Only 6 of the 48 lifeboats were successfully launched; everyone else was trapped in the ship or forced to fend for themselves in the frigid water. Rescue boats took about 2 hours to reach the survivors. Despite the rescuers’ best efforts, only about 760 people were saved—a little over a third of the number of those originally on board.

The sinking of the Lusitania caused international outrage toward Germany, especially in America, which had lost 128 of the 159 of its citizens on board. Though the sinking of the Lusitania didn’t directly cause America to enter the war (it wouldn’t enter for another two years), it did turn public opinion against Germany, and when America finally entered the war, Germany’s submarine attacks were a leading reason.

Want to learn more about the Lusitania? Start a search on Fold3.

Erik Larson’s new book, Dead Wake, delves into the last voyage of the Lusitania. I’ve just started the book myself and can’t wait to hear his telling of the event.

I read Eric Lawson’s book and it was very good. Learned many new things. It’s an easy read too.

The Lusitania was carrying many tons of munitions at the time of her sinking. This was in violation of treaties of the time. President Wilson attempted to and almost succeeded in having all the warnings by the German government censored and taken out of the newspapers.

Near the coast of Ireland the vessel that had escorted the Lusitania across the Atlantic was ordered away and the Lusitania was ordered to slow to a speed slower than German U boats.

Check the “Dangerous History Podcast” for more on this story

The Lusitania had two cargo manifests, a dumby one that did not show munitions, and the one that was sealed for 90 years that did show munitions for Britain. The second explosion was the munitions exploding and blowing out the bottom of the ship causing it to sink in 18 minutes. Churchhill ordered the ship to slow down know that do to the number of wealthy americans on board, this would cause us to step up our efforts and eventually enter the war. Britain was losing the war at that time. This is all documented fact.

This involved a terrible loss of life, but pales in comparison with the deliberate sinking of the William Gustloff. 9,343 lost their lives when the Bolsheviks sank this rescue ship. Few thought something like this would happen, but we now know that the war plan of the allies was to kill as many Germans as possible, and if all Germans were exterminated, that would be the best outcome. 300,000 were killed in the bombing of Dresden by the Brits and Americans as just a small part of the overall bombing campaign. Americans killed far more German soldiers after the war than during in the Eisenhower death camps. There’s much more to learn about Allied war crimes in the book, “Hellstorm.”

Churchhill???? I would say wrong war.

Considering Churchill was head of the Admiralty in WWI, so yes, he would have played a part. Whether one believes that conspiracy theory, however, is a different matter.

For those who wonder if there was a conspiracy to allow the Lusitania to be sunk, here’s a good article found at http://www.rmslusitania.info/controversies/conspiracy-or-foul-up/.

Personally, I doubt there was one but I don’t rule it out.

Conspiracy or Foul-Up?

Did Winston Churchill engineer a conspiracy to sink Lusitania and bring the United States into World War I?

The speculation about the conspiracy theory comes from a letter Winston Churchill sent to Walter Runciman, the president of Britain’s Board of Trade. In this letter, Churchill wrote the following:

It is most important to attract neutral shipping to our shores in the

hope especially of embroiling the United States with Germany . . . .

For our part we want the traffic — the more the better; and if some of

it gets into trouble, better still.

Of course, the obvious hole in this argument is that while the United States was neutral, Lusitania was clearly a British ship and not “neutral shipping.”

One can also question the lack of action on behalf of the Admiralty in light of the Admiralty’s previous records of looking after Lusitania. Lusitania was a symbol of national prestige. Naturally, more privileges were granted to her than to any other ship.

When Lusitania was scheduled to arrive in Liverpool on 6 March 1915, Trade Division signalled Lusitania at Cunard’s request, relaying,”Owners advise keep well out. Time arrival to cross bar without waiting.”

Admiral Henry Oliver also sent two destroyers, HMS Laverock and HMS Louis to receive and escort Lusitania, and sent Q ship HMS Lyons to patrol Liverpool Bay, even with the shortage of available destroyers at the time. Captain Dow, not wishing to disclose his location to listening Germans, steamed Lusitania into Liverpool by herself.

Compare this with Lusitania‘s last crossing, where the Admiralty took no precautions to protect Lusitania.

No specific orders, no escorts, no Q ships. Even when the destroyers Lucifer, Legion, Linnet, and Laverock were sitting idly at Milford Haven, Wales, and were available for such a job. Even when the Admiralty knew full well of the danger Lusitania was heading into, the Admiralty did not relay the news of the sinkings of Earl of Lathom, Candidate, Centurion, and the attempt on the Cayo Romano, to Lusitania despite the fact that these incidents were reported to the Admiralty and specifically requested to reach Lusitania.

Twenty-three merchant vessels had been torpedoed in the general area Lusitania was steaming through since Lusitania left New York, and absolutely no word of any of these attacks were relayed to Lusitania. Radio silence would not have been an excuse, as Admiral Oliver could have alerted Vice Admiral Coke at Queenstown of the danger if he could not reach Lusitania.

Furthermore, radio exchanges between Lusitania and the Admiralty from 5 to 7 May remain classified to this day. This has led to speculation that Captain Turner had requested to divert Lusitania north around Ireland and through the North Channel and was denied. The North Channel route was cleared of mines by 15 April 1915 and the Admiralty could permit merchant ships to pass through if given the OK. Being denied this route, Captain Turner would have had to take Lusitania south, where she was torpedoed.

The fact that no correspondence between Churchill and First Sea Lord Jacky Fisher from the time of Lusitania‘s last crossing has survived has also fueled speculation that something was going on.

The precautions taken to ensure Lusitania‘s safety in March and the safety of other vessels since the Germans declared the waters around Britain a war zone were conspicuously absent on Lusitania‘s last crossing. The Admiralty had ten days to aid Lusitania and did not. From this, one would come to two conclusions:

The Admiralty did plan to expose Lusitania to danger in the off

chance that a German submarine would attack her, enraging the

American public.

The Admiralty fouled up, and their gross negligence resulted in a

tremendous loss of life.

However, one must realize that if any conspiracy happened, it cannot be designed in great detail and must leave a great deal to chance. The British codebreakers of Room 40 did not always have the most updated locations of German submarines, and the U-boats of the First World War did not have reliable aim. The chances that any torpedo would hit the very spot that would have dealt Lusitaniaa fatal blow were impossibly remote; in fact, if Schwieger had not overestimated Lusitania‘s speed by four knots, the torpedo would have struck elsewhere, and the ship probably would not have sunk.

Any possible conspiracy could only have been one of withholding information from Lusitania and leaving chance to put the ship into harm’s way. A successful U-boat attack would require the submarine to be, not within a few miles, but within a few hundred yards of Lusitania and on a bearing suitable for attack. Furthermore, for a ship as meticulously designed as Lusitania, the plotters probably only imagined an injured but stable Lusitania limping into Queenstown, hoping that the attempt alone would anger the United States into joining the Allies. A complete sinking with tremendous loss of life, however, would have been unthinkable and must have horrified the plotters, spurring them into a hasty cover-up.

One must realize that in the lack of hard evidence, any suspicion of a government conspiracy is only circumstancial. That, in and of itself, is not proof of any government plot.

A foul-up, however, was also possible. At the time, the Admiralty had been preoccupied with Churchill’s brainchild, the Dardanelles campaign, Lusitania must have only been an afterthought to the men of the Admiralty. This situation was worsened by the fact that both Churchill and First Sea Lord Jacky Fisher kept information to themselves and were known to micromanage. Their refusal to delegate jobs led to Churchill’s and Fisher’s subordinates being ill-equipped to act on their own, leading to no one acting, or even consider acting, to protect Lusitania. Furthermore, it would have been unthinkable for a ship as fast as Lusitania to be attacked, let alone sunk, so actions to protect her might not have been deemed necessary.

A foul-up could also explain the cover-up: if the truth of such a foul-up had been made public, it would have been a tremendous national humiliation played out in front of the Central Powers and a blow to British morale. As it was, no one in the upper ranks of the Admiralty was held accountable for this bungling, and Churchill and First Sea Lord Jacky Fisher were eager to push the blame onto Captain Turner.

The idea of Churchill trying to pull the United States into the war would be unlikely due to the following reasons:

In 1915, the United States had not yet mobilized for war, and Britain was dependent on the US for the British Army in France. If the US had declared war right after the Lusitania‘s sinking, the supplies that had once been going to Britain would have stayed in the US, leaving the British without ammunition to fight the Germans.

Churchill and Fisher were known to keep information to themselves and micromanage the affairs of Room 40. Fisher was close to a nervous breakdown at the time and Churchill was in France at the time of Lusitania‘s sinking. If Churchill had wanted Lusitania sunk, such a plan could not have happened without his explicit approval, and he would have stayed in Britain to supervise the plot instead of being in France.

Diana Preston advances a theory that, without Fisher and Churchill, Captain William Reginald Hall could have masterminded such a plot. Captain (later Admiral) Hall was known to use cloak-and-dagger tactics, had access to all the relevant decodes of Room 40, and capable of acting independently of Fisher and Churchill. Whether he could have executed such a plan without Churchill’s knowledge and approval, however, remains speculative.

my grandfather was on the lucitania as a burser boy and survived, but the schock of being in the freezing water turned his hair grey. He was very young then. Arthur Murphy.

DOES ANYONE KNOW ABOUT THE LACONIA. MY MOTHER CAME OVER FROM IRELAND ON THE LACONIA. LATER ON THIS SHIP WAS ALSO SUNK BY A GERMAN SUB. NEED MORE INFO ON THE LACONIA

I know it was Cunard’s first ship built for transatlantic service. There is a lot of information around about it, but it was something I had to study, as I work with Cunard quite a bit. This video has some great stills and information about it: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K4S2miocIvM

My grandfather was a Corporal with the 2nd American unit sent to France in 1917 when the U.S. finally declared against Germany in 1917. They were then and later called the Yankee Division. my grandfather kept a diary of his first 6 months or so in France including his trip across the Atlantic on a Canadian ship and his trip by railroad down from their arrival in Scotland to England as his next 6 months in France.

a detail I did not know until I read a copy of my grandfather’s diary was that there were “practice” trenches built some distance from the front lines, supposedly out of artillery range of the forward German trenches where new troops were kept and given “training” to teach them what it would be like when they were moved up to the front line trenches.

As my Grandfather’s diary reveals, although the military supposed that these “practice” trenches were supposedly out of artillery range of the German guns, they obviously were not.

My grandfather’s diary stops when he was sent forward to the front line trenches as it was a practice of the British and French not to allow direct reports to be written home from those trenches, although of course some soldiers did smuggle material to write letters home.

Their was an active confiscation of writing material from front line fighters by the British, French, and later American commanders when they went forward to the front line trenches.

Hi Robert,

May I ask whether your grandfather’s diary gives much detail on his time in Britain? For example where he went and his observations on Britain and the British.

I ask as I’m working on the history of Winchester during the Great War and the camps here, and in nearby Romsey, were used by the AEF as “Rest Camps” prior to departure for France (often from the nearby port of Southampton) and any original references would be very interesting and useful.

If you can help in any way it’d be very much appreciated

Yours sincerely

Dave

Some errors in the comments above need to be corrected. Although Lusitania was operating with only three of its four boilers, its speed was still twice the speed of the U-20 on the surface, and almost three times as fast as the underwater speed of the U-20.

Yes, Lusitania was carrying ammunition, but ammunition was not the cause of the second explosion– according to Ballard, the ammunition is still on the sunken ship, and did not explode. Lusitania was a ship of the Royal Navy, and used steam turbines to drive the propellers. Although controversy still exists, 100 years later, the most likely cause of the second explosion less than a minute after the torpedo hit is the rupture of the steam lines.

The most detailed account about the Lusitania sinking is probably found in the book, “Lusitania: an epic tragedy,” by Diana Preston.

There is a couple of points that need to be brought into this discussion. The first is the speed of the Lusitainia had to be reduced as it approached the Liverpool shores because of a heavy fog. The density of the fog not only demanded that the Lusitainia maneuver at a slow speed but required them to use their fog horn as well.

Secondly, the fog also reduced the visibility of the lookouts. A large, fast ship as the Lusitainia at sea in fair weather would have a good chance at sighting one or more torpedoes at a much further distance allowing the ship to take defensive action by changing its heading out of the path of the torpedoes. The slow speed and reduced visibility prevented the Lusitainia from taking proper evasive action even when the spotter first observed the incoming torpedoe.

The comments to the above Trevor article strongly encourage a new and honest enquiry after a century of lies and misinformation. As Rupert Gude on ‘Centenary News’ correctly stated: “… the UK Government has never come clean about the use of the Lusitania to carry munitions. Until a nation confronts its past with a clear and open mind it will continue to delude itself.” (see: http://www.centenarynews.com/article/latest-book-review—dead-wake). And indeed, it is really a shame that even after 100 years and all the proven facts about ‘babies and bombs’ suggesting a very different Lusitania narrative than the above article, there has still not been the slightest admission, no public examination or any apologise for all the denials and deceit, for all distress inflicted upon so many innocent people and for all the devilish propaganda virulent till today. It is really unbelievable, a shame. Since the supplemental cargo manifest has reemeerged (thanks to Mitch Peeke), proving the shocking evidence that Lusitania was in fact used as an ‘express ammunition carrier’ with a human shield, there is enough reason for a new and fact based punitive damages trial. Who is afraid of that?

But don’t forget, in the Daily Express, March 1933, the headline read: “JUDEA DECLARES WAR ON GERMANY”…so that is the true start of WW2.

Here in our small town we had 2 soldiers that were on the Lusitania and survived.

They were a part of a troop movement, how many men I don’t remember, but there was some hush hush that denied that. Just my 2 bits worth.

My aunt was on board the Lusitania and survived the sinking ..

My aunt when I was on the Lusitania and survived the sinking.

please unsubscribe

Please un

My grandmothers relative died on the luisitania. Body was buried in queenstown (cobh) in a common grave,left relatives bitter to their end. I am sure many were disappointed with cunard & the english govt.

My great uncle and his cousin tried to join the Navy after he sinking. He wound up in the Marines and was killed in the Battle of St Mihiel in late 1918

As I remember, Churchill was the senior member of the board of review for the Admiralty and, in the US, the Naval board reporting on the sinking was headed by the Undersecretary of the Navy: Franklin Roosevelt. That neither board mentioned the munitions on board or that they might have had some effect in the rapid sinking smacks of a cover-up involving both countries.

I didn’t realize that the U.S. didn’t enter WWI until 2 years after the sinking. I had thought for y-e-a-r-s that that sinking jump-started our entry into WWI. Boy, what I have learned today reading this article.