As we celebrate America’s independence this month, learn more about the people who made it possible by exploring Fold3’s Revolutionary War Collection for free July 1st to 15th.

Popular titles for finding Revolutionary War ancestors include:

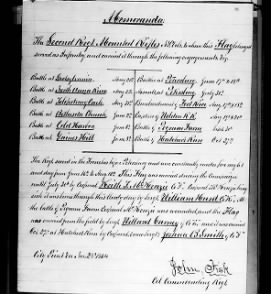

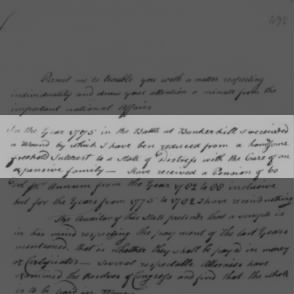

- Revolutionary War Pensions

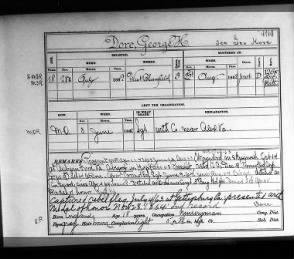

- Revolutionary War Service Records

- Revolutionary War Rolls

- Final Payment Vouchers Index for Military Pensions, 1818–1864

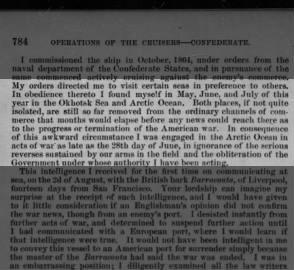

If you’re interested in the historical aspects of the war, you can explore the captured vessels prize cases, Revolutionary War Milestone Documents, the Pennsylvania Archives, Constitutional Convention Records, and the papers and records of the Continental Congress, among others.

Full access to the Revolutionary War collection can help you find even more information on the people or events you’re researching. For example, let’s say you’re researching your ancestor James Morris of Connecticut. You can learn from his Revolutionary War pension file that he served in the Battle of Germantown, where he was taken prisoner of war for three years.

But your research doesn’t have to stop there. If you wanted to discover more about Morris than you found in his pension file, you could look in the Revolutionary War Rolls to find him listed on a muster roll during his time as a prisoner. If you were interested in learning more what Morris’s time as a prisoner of war may have been like, you could search for accounts of other Revolutionary War POWs—in places like the pension files, the Pennsylvania Archives, the papers of the Continental Congress, and elsewhere.

But your research doesn’t have to stop there. If you wanted to discover more about Morris than you found in his pension file, you could look in the Revolutionary War Rolls to find him listed on a muster roll during his time as a prisoner. If you were interested in learning more what Morris’s time as a prisoner of war may have been like, you could search for accounts of other Revolutionary War POWs—in places like the pension files, the Pennsylvania Archives, the papers of the Continental Congress, and elsewhere.

Or if you’d rather flesh out your understanding of the battle Morris was captured in, then you could read George Washington’s own account of the Battle of Germantown in the papers of the Continental Congress.

There’s a lot to discover in the Revolutionary War Collection. Start your own exploration here.